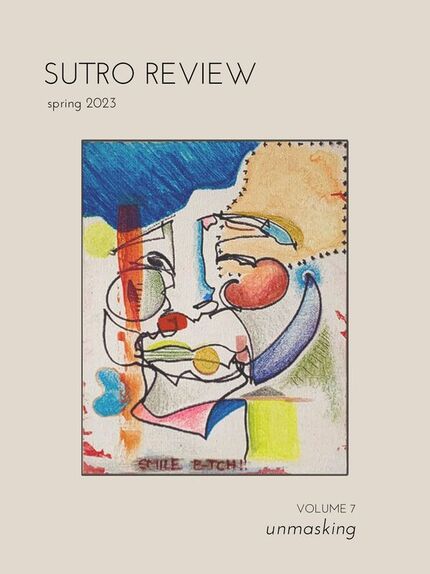

Sutro Review 2023

SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Personal Narratives

Marcus Alexander Isidro – The Flavors of My Language

Nate Newman – A Walk

Ashmita Sapkota – Unmasking and Rediscovering Normalcy

Faye Mayer – The Light Switched On

Donna Pham – Am I a Filial Son or Daughter?

Reflections on Career Pathways and the Future

Mallika Mahendru – Love on the Brain: An Introspective Analysis of my Major, Identity, and Future

Zachary Espy – Refined and Tempered Like Steel

Critical Analysis and Investigative Pieces

Nia Wochnowski – The Urge to Define Beauty

Gabriella Melton – An OREO Cookie, a Yellow Wallpaper, and a Queer Handmaiden Walk Into a Comparative Essay and Find Common Ground in the Female Experience

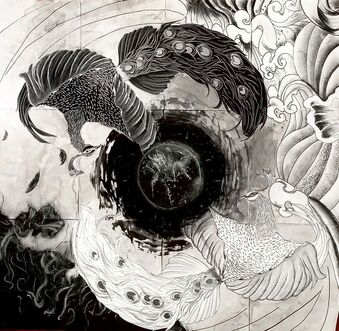

Osvaldo Salazar – Born What Way? Trapped in the Portal of Perpetual Rebirth

Poetry

Caitlin Darke – Houseplant and wifi

Alexiz Romero – burning

Atzeli Ramirez – That One Year

Photography & Artwork

Han Le (Cover Artist) – Before Human, Don't Give Up On Me, and Mind

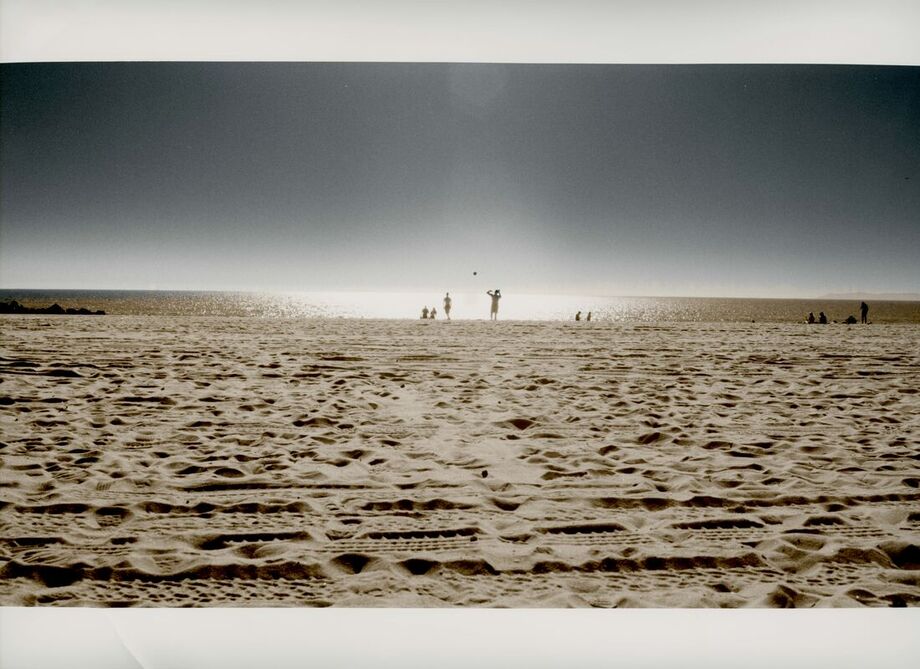

Zachary Greenberg – The Great Masturbator, Portrait of a Human with a Rhinestone Veil and What We Aim For

Grace Scerni – Take a Closer Look and Sweet

About the cover: "Smile" by Han Le (artist name HAAN): The phrase "Smile, B*tch!" might not be the most appropriate or respectful way of reminding someone to stay positive and to keep smiling, but this language is powerful. We've all been through a lot of changes and challenges, especially post-pandemic, so I feel it's always necessary to remind ourselves and our loved ones to appreciate life, find joy in the little things, and never forget that a smile can be so colorful. See bio and more art by Han Le in the issue below.

Personal Narratives

Marcus Alexander Isidro – The Flavors of My Language

Nate Newman – A Walk

Ashmita Sapkota – Unmasking and Rediscovering Normalcy

Faye Mayer – The Light Switched On

Donna Pham – Am I a Filial Son or Daughter?

Reflections on Career Pathways and the Future

Mallika Mahendru – Love on the Brain: An Introspective Analysis of my Major, Identity, and Future

Zachary Espy – Refined and Tempered Like Steel

Critical Analysis and Investigative Pieces

Nia Wochnowski – The Urge to Define Beauty

Gabriella Melton – An OREO Cookie, a Yellow Wallpaper, and a Queer Handmaiden Walk Into a Comparative Essay and Find Common Ground in the Female Experience

Osvaldo Salazar – Born What Way? Trapped in the Portal of Perpetual Rebirth

Poetry

Caitlin Darke – Houseplant and wifi

Alexiz Romero – burning

Atzeli Ramirez – That One Year

Photography & Artwork

Han Le (Cover Artist) – Before Human, Don't Give Up On Me, and Mind

Zachary Greenberg – The Great Masturbator, Portrait of a Human with a Rhinestone Veil and What We Aim For

Grace Scerni – Take a Closer Look and Sweet

About the cover: "Smile" by Han Le (artist name HAAN): The phrase "Smile, B*tch!" might not be the most appropriate or respectful way of reminding someone to stay positive and to keep smiling, but this language is powerful. We've all been through a lot of changes and challenges, especially post-pandemic, so I feel it's always necessary to remind ourselves and our loved ones to appreciate life, find joy in the little things, and never forget that a smile can be so colorful. See bio and more art by Han Le in the issue below.