Sutro Review 2022

SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition

SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition

|

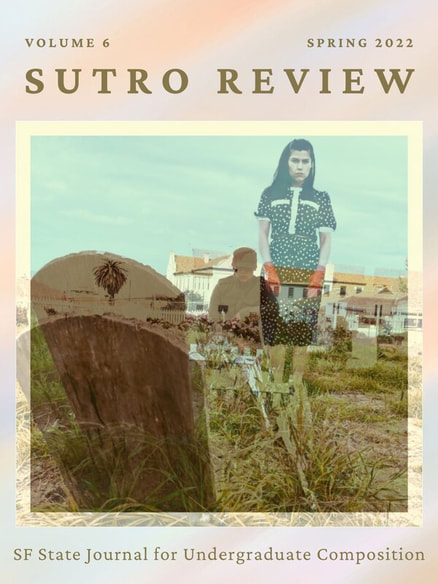

Cover Art: "424" by Ixchel Acosta

|

Dear readers,

We are delighted to present the sixth annual volume of Sutro Review: SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition, an academic journal written, edited and produced by SF State students. In it you will find writing, photography and artwork from some of our most promising undergraduates. During such a tumultuous year, we are grateful to everyone who took the time to submit their work for consideration. With so much upheaval in our world, from war to inflation to climate change, and an ongoing pandemic, it became clear as we read submissions, how important it is to have a creative outlet and interests that sustain us and get us through stressful times. We have grouped the writing into four main categories: personal narratives, reflections on career pathways, investigative pieces, and essays related to education and learning. Whether you want to read about how someone found their cultural identity or how a song relates to the environment or the ways people find community, there is something for you here. Thanks to all the professors who encouraged their students to submit their work and a very special thank you to Tara Lockhart for being such an unwavering champion of Sutro Review and promoting it continually throughout the year. Last but never least, we’d like to thank the SF State University Instructionally Related Activities Fund for making Sutro Review possible. We hope you enjoy the issue! Stay healthy and read on, Sutro Review Editors Faculty Advisor: Robin Meyerowitz Editors: aleah antonio Sonia Leah Getz Gabriella Napolitana Melton |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Writing

Personal Narratives

Ixchel Acosta – My Ritual With Nature

Kailey Flores – Glitters of Healing

Sydney Wagman – White Butterflies

Reflections on Career Pathways

Ev Guzman – Finally I'm Running Towards Myself, Not Away

Yvone Perez – The Dangerous Comfort Zone

Nyla Raffety-Williams – Experiences with Racial Identity Development

Investigative Pieces

Mayer Adelberg – Exploring the Intersection of Ecomusicology, Sustainability, and Preservationism

Jared Bautista – Mined Your Business

Nathan Burns – Fighting Isolation Through Community

Essays on Learning and Education

Annie Dang – Critical Reflections on My Education

Fay Harris – Growth Mindset and Deliberate Practice: Success Strategies and How I Apply Them

Photography & Artwork

Ixchel Acosta

Breanna Barton-Shaw

Kunj Sevak

About the cover: “424” was taken by Ixchel Acosta in the Presidio, where approximately 2000 military families lived in the 1950s. In the photo, Acosta depicts one aspect of their lives: having a pet.

I pass by this pet cemetery in the Presidio two to three times a week on a run that my sister and I have done since the beginning of last year. Not until I walked this path did I realize that the gate was open. I went in and looked around, as I have always been intrigued by cemeteries. They represent a life that once was. The style, the decorative cut, and the age of the stones are always so cool to look at. It reminded me of watching Stephen King's Pet Semetery when I was growing up. Having this movie in mind helped me to create an eerily depicted photo. 424 represents the number of tombstones that are present in the cemetery.

I wanted my piece to depict the past, which is invisible to the eye, but we all know it exists. I dressed in military garb for the male and a vintage polka-dot dress for the female. The transparent feature allows me to merge the bodies of a husband and wife and give the idea that they are past lives that have come back to visit their pets. I chose to use a color that mimics photos of the past, and a white border to give it that extra detail, something that I have always loved about old photos.

Writing

Personal Narratives

Ixchel Acosta – My Ritual With Nature

Kailey Flores – Glitters of Healing

Sydney Wagman – White Butterflies

Reflections on Career Pathways

Ev Guzman – Finally I'm Running Towards Myself, Not Away

Yvone Perez – The Dangerous Comfort Zone

Nyla Raffety-Williams – Experiences with Racial Identity Development

Investigative Pieces

Mayer Adelberg – Exploring the Intersection of Ecomusicology, Sustainability, and Preservationism

Jared Bautista – Mined Your Business

Nathan Burns – Fighting Isolation Through Community

Essays on Learning and Education

Annie Dang – Critical Reflections on My Education

Fay Harris – Growth Mindset and Deliberate Practice: Success Strategies and How I Apply Them

Photography & Artwork

Ixchel Acosta

Breanna Barton-Shaw

Kunj Sevak

About the cover: “424” was taken by Ixchel Acosta in the Presidio, where approximately 2000 military families lived in the 1950s. In the photo, Acosta depicts one aspect of their lives: having a pet.

I pass by this pet cemetery in the Presidio two to three times a week on a run that my sister and I have done since the beginning of last year. Not until I walked this path did I realize that the gate was open. I went in and looked around, as I have always been intrigued by cemeteries. They represent a life that once was. The style, the decorative cut, and the age of the stones are always so cool to look at. It reminded me of watching Stephen King's Pet Semetery when I was growing up. Having this movie in mind helped me to create an eerily depicted photo. 424 represents the number of tombstones that are present in the cemetery.

I wanted my piece to depict the past, which is invisible to the eye, but we all know it exists. I dressed in military garb for the male and a vintage polka-dot dress for the female. The transparent feature allows me to merge the bodies of a husband and wife and give the idea that they are past lives that have come back to visit their pets. I chose to use a color that mimics photos of the past, and a white border to give it that extra detail, something that I have always loved about old photos.

Personal Narratives

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND PHOTOGRAPHER: Ixchel Acosta is in her senior year here at SF State. She wrote this piece in her first semester as a junior in her GWAR course. Professor Nico Peck assigned the class to explore the rhetoric of ecology through the lens of ecosexuality and (re)claim/decolonize their relationship with nature. Her take away: if we treat the earth as our lover, the world would be better taken care of. |

Ixchel Acosta

My Ritual With Nature

My Ritual With Nature

I have a consistent workout that I do three to four days a week. Really, it's my excuse to indulge in nature. I need it to fuel me, it is my ritual. Throughout this ritual, I react with and to my (lover) earth. Through this reflection, I have learned about the relationship that I have come to have with nature, the communication that exists between us, the beauty she allows me to take in, and how I need this ritual to complete me.

Nature communicates with me, she tells me what to wear or even if I can complete my ritual for the day. I open my door and test the temperature; I look at the sky and it helps me to decide, I dress accordingly. I pop in my headphones and I will typically choose Beyonce, or Billie Eilish to serenade me. They help me get in step and I run to their beat. The music and dancing of the trees keep me moving. My journey starts on Lyon Street and Sutter, the trees that line the block consist of Cherry Blossoms. The colors of the buds are beautiful, pink, and soft. Depending on the temperature, at times, I breathe a little harder. The cold definitely gets to me, my lungs and throat burn. San Francisco is not flat, as we all know, so up the hills, I climb. The incline starts out very small and the last one almost kills me. Sweating, I get consistent bursts of natural air conditioning, she’s enticing. Once I get to the top I receive my reward: the view of the San Francisco Bay, the differences in the blue of the sky and the water paint a beautiful ombre picture. The Presidio lives to the left, I am tempted to enter. The Lyon Street steps are home to many: fellow workout nerds, pups, and tourists. They all have a ton of energy flowing through them, all different. Inhaling and exhaling as they run up and down the stairs. Wagging of tails. Excitement, maybe visiting for the first time. I run down the steps and in front of me is the biggest redwood tree, she constantly reminds me of how small I am.

Nature communicates with me, she tells me what to wear or even if I can complete my ritual for the day. I open my door and test the temperature; I look at the sky and it helps me to decide, I dress accordingly. I pop in my headphones and I will typically choose Beyonce, or Billie Eilish to serenade me. They help me get in step and I run to their beat. The music and dancing of the trees keep me moving. My journey starts on Lyon Street and Sutter, the trees that line the block consist of Cherry Blossoms. The colors of the buds are beautiful, pink, and soft. Depending on the temperature, at times, I breathe a little harder. The cold definitely gets to me, my lungs and throat burn. San Francisco is not flat, as we all know, so up the hills, I climb. The incline starts out very small and the last one almost kills me. Sweating, I get consistent bursts of natural air conditioning, she’s enticing. Once I get to the top I receive my reward: the view of the San Francisco Bay, the differences in the blue of the sky and the water paint a beautiful ombre picture. The Presidio lives to the left, I am tempted to enter. The Lyon Street steps are home to many: fellow workout nerds, pups, and tourists. They all have a ton of energy flowing through them, all different. Inhaling and exhaling as they run up and down the stairs. Wagging of tails. Excitement, maybe visiting for the first time. I run down the steps and in front of me is the biggest redwood tree, she constantly reminds me of how small I am.

Throughout my ritual I breathe in, I take in, I absorb, and I appreciate all that I have been given.

I continue down Lyon Street and I am allowed to enter the gates of the Presidio. Another beautiful treat that I am allowed to see. The smell of the Pine trees is amazing, especially when they are being manicured. I am surrounded by a variety of greens, browns, and blues. My path takes me up and down the Presidio and I end up at the water's edge. I take out my headphones and listen to all that is natural. I sit and enjoy the crashing of the waves, the dogs running in and out of the water. I believe they enjoy it even more than we could ever imagine. I take the water path and head home through the Palace of Fine Arts. I see ducks, birds, and turtles, and the blue sky above displays the birds like a portrait. My eyes have been pampered.

Throughout my ritual I breathe in, I take in, I absorb, and I appreciate all that I have been given. I receive my energy from being outside. The days that I do not make it out, I feel that they have been wasted. I need it. bell hooks (1996) shares a quote from Chief Seattle in 1854 that resonates with me, “How can you buy or sell the sky, the warmth of the land? The idea is strange to us. If we do not own the freshness of the air and the sparkle of the water, how can you buy them? Every part of this Earth is sacred to my people...We are part of the earth and it is part of us”(364). When I take this path and perform my ritual, I constantly think how lucky I am, not required to pay a fee. This beauty is here for all of us to enjoy. I am fortunate.

This ritual is only mine, the experience and feelings that I share with my (lover) nature are only for me. I indulge in nature, we communicate, she shares her beauty and she completes me.

Works Cited

hooks, b. (1996). Touching the earth. Sisters of the Yam–Black Women and Self.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kailey Flores is a first year student studying Broadcast and Electronic Communication Arts with a minor in Queer Ethnic Studies. Moving from Riverside out to San Francisco, they often found themselves in situations where they were looking for home in this new city. This piece is a love letter to The Mission, where they found home in this instance and many more. |

Kailey Flores

Glitters of Healing

Glitters of Healing

A couple of weeks ago I was out in The Mission district with a friend in Balmy Alley turned Lovers Lane for Valentine's Day weekend. We were sharing some thoughts over lunch, revisiting our childhood idols.

I asked her, “Who did you want to be when you grew up? Who were the women you looked up to?”

She began detailing to me an all-too-familiar story of wanting to be a kind of pretty that was deeply tied to a coveted whiteness. She expressed growing up with white women and eurocentric beauty as her pillar of THE ultimate beauty. She talked about how she thought the only acceptable type of beauty was locked into white skin, blue eyes, blonde straight hair and how she wanted each of these features eagerly although she couldn’t have told you why if you asked. I began to think about who I looked to during that time as a pillar of beauty and who I hoped to look like as I grew and matured. They were also white women. I imagined looking like Miley Cyrus (or more specifically Hannah Montana) at the age of eight or nine. I imagined my spontaneous adoption of her blue eyes and blonde hair, having a similarly small figure, or even her pale complexion. I remembered having not only an envy for these features but an additional distaste for the features I already owned. I never saw cool teen girls on tv with brown skin, hairy arms and upper lips and chubby awkward bodies. Girls like me never made it on Disney, we did not exist on screen.

I asked her, “Who did you want to be when you grew up? Who were the women you looked up to?”

She began detailing to me an all-too-familiar story of wanting to be a kind of pretty that was deeply tied to a coveted whiteness. She expressed growing up with white women and eurocentric beauty as her pillar of THE ultimate beauty. She talked about how she thought the only acceptable type of beauty was locked into white skin, blue eyes, blonde straight hair and how she wanted each of these features eagerly although she couldn’t have told you why if you asked. I began to think about who I looked to during that time as a pillar of beauty and who I hoped to look like as I grew and matured. They were also white women. I imagined looking like Miley Cyrus (or more specifically Hannah Montana) at the age of eight or nine. I imagined my spontaneous adoption of her blue eyes and blonde hair, having a similarly small figure, or even her pale complexion. I remembered having not only an envy for these features but an additional distaste for the features I already owned. I never saw cool teen girls on tv with brown skin, hairy arms and upper lips and chubby awkward bodies. Girls like me never made it on Disney, we did not exist on screen.

I often revisit that younger me who wanted nothing more than to erase who I undeniably was.

After exchanging our sharp distaste for the influences of our younger selves, I followed with another question.

“Who did you think you’d be in your twenties?”

By this, I meant beyond that first white ideal. Who did she think she would be not at the age of eight or nine, but at the age of 18 or 19?

She described a woman who looked a lot like her. A woman brown and proud, a woman with her own sense of style. A woman who looked a lot like all of the women at this event. Like the women in both of our lives; moms, tias, abuelas, primas.

I remember asking this question because I wondered if being in this space with women dressed all the way out and showing all the way up filled her with as much joy as it did I. I wanted to know if her cheeks were aching under her mask the same way mine were due to a chronic smile that had found its way onto my lips the minute we had arrived just in eyeshot of Balmy Alley. I wanted to know if seeing brown women adorned in tattoos, beautiful jewelry, killer makeup and the flyest outfits was her dream as much as it was mine. I wanted to know if that younger version of her who could not see the beauty in her own skin was also looking in awe at this display of beauty in which she was now undeniably intertwined. I wanted to know if she felt just as at home as I did.

At this point in my living in San Francisco it had become seemingly hard to deny that I felt out of place in many of the spaces around the city. But in this alley I was home and that was equally undeniable. I swayed from booth to booth with nothing but the greatest smile painted across my face and a buzzing childlike joy overtaking my every step. Little awes and “I’m so happy’s” kept escaping from between my grin. My head was filled with the echoes of oldies and cumbias spinning at the other end of the alley as I watched all the women dancing and singing together with no care for anything but for their steps and this rhythm in the middle of this alley. I was transported back to memories of family parties and events in my hometown. I was home.

I often revisit that younger me who wanted nothing more than to erase who I undeniably was. I revisit her as someone who dreams of being one of these brown women who shows all the way up and takes up every last inch of their respective space in her statement earrings, tattoo adorned skin, sharp eyeliner and dark lips. There is a special healing that takes place every time I get to see women being joyful in this way or telling their stories or accomplishing their wildest dreams. Every time I am surrounded by women in this way, little pieces of that younger me are not only healed but returned to me to hold and re-examine. Similarly, that younger me is returned to my arms to be held and her wounds to be kissed. It is a reminder as I move through life learning and unlearning things that do and do not serve me of my undeniable right to be celebrated and loved. I often wonder what an eight or nine year old me would say if she saw who it is that I have grown up to be. I now believe she would be in awe of her features, her statement earrings, her tattoo adorned arms and mostly the way she takes up her space with no hesitation.

Josephine

Ixchel Acosta

Ixchel Acosta

About the photos: Created for COMM 556 Performance Art: Aesthetic Communication Criticism with Dr. Colleen Kim Daniher for the Alter Ego Portrait Performance assignment.

Acosta writes, "My Alter ego is Josephine Bustamante, born in 1913. Growing up in Santa Monica, she dreamt of becoming an actress. Her grandmother would scrounge up every penny she could to put her in dance classes at the age of five and made every costume for her to perform in. Growing up during WWI and WWII, the options for Mexican women in the workforce were taking care of someone else’s home and/or their children. This was not what she wanted, and her grandmother had bigger dreams for her. Her first big role was a chorus girl in Cover Girl, starring Rita Hayworth, her Idol. Josephine is always in the limelight, surrounded by Hollywood stars. On the arms of well-dressed actors, sharing stories while powdering her nose at the parties held in mansions. Always dressed to the nines.

When Josephine takes the stage, the world becomes her audience. Not until I sat down to think about my alter ego did I realize that she has always been a part of me. I am a people person. I get my energy from others. I love being out and about and dressing up. I have always loved this era, and it’s because of my grandmother, Josephine. Rita Hayworth was her favorite. As Josephine, I am way more confident. I hold my posture in a very different way. I’d say a little more feminine and quite flirty. When I get dressed up to go out, this is the style I prefer, not completely, but she’s in there. I actually take on a different persona. Even depending on where I am, I imagine myself as this person and the room sometimes actually changes as well. I think that I am a pretty confident person normally, but Josephine gives me a push. I can describe it as if I time traveled, and it’s just one day that I get to be this person, so I live it fully.

Josephine works with imagery depicting an American actress and dancer in the 1940’s, during a photo shoot. I have dressed in a 1940’s style vintage grey dress with embroidered black flowers on the right side. A dress that was purchased from the Golden Hour, a vintage shop in San Francisco. The night before, I did a pinwheel wet set (typical in the 1940s) on my hair and went to bed in a scarf wrapped around my head. The next morning I was transformed into Josephine. I woke up, combed out my hair, and styled it. I picked out my dress from two options. I applied a Victory Red lipstick by Besame cosmetics, a company that takes inspiration from worn colors during certain eras. A color inspired this particular lipstick from 1941. I applied black wing for my eyeliner and colored in my brows. I choose to use a photo style reminiscent of a black and white photo that added color. I wanted this photo to look like a portrait that would be autographed and given to fans of Josephine Bustamante."

Acosta writes, "My Alter ego is Josephine Bustamante, born in 1913. Growing up in Santa Monica, she dreamt of becoming an actress. Her grandmother would scrounge up every penny she could to put her in dance classes at the age of five and made every costume for her to perform in. Growing up during WWI and WWII, the options for Mexican women in the workforce were taking care of someone else’s home and/or their children. This was not what she wanted, and her grandmother had bigger dreams for her. Her first big role was a chorus girl in Cover Girl, starring Rita Hayworth, her Idol. Josephine is always in the limelight, surrounded by Hollywood stars. On the arms of well-dressed actors, sharing stories while powdering her nose at the parties held in mansions. Always dressed to the nines.

When Josephine takes the stage, the world becomes her audience. Not until I sat down to think about my alter ego did I realize that she has always been a part of me. I am a people person. I get my energy from others. I love being out and about and dressing up. I have always loved this era, and it’s because of my grandmother, Josephine. Rita Hayworth was her favorite. As Josephine, I am way more confident. I hold my posture in a very different way. I’d say a little more feminine and quite flirty. When I get dressed up to go out, this is the style I prefer, not completely, but she’s in there. I actually take on a different persona. Even depending on where I am, I imagine myself as this person and the room sometimes actually changes as well. I think that I am a pretty confident person normally, but Josephine gives me a push. I can describe it as if I time traveled, and it’s just one day that I get to be this person, so I live it fully.

Josephine works with imagery depicting an American actress and dancer in the 1940’s, during a photo shoot. I have dressed in a 1940’s style vintage grey dress with embroidered black flowers on the right side. A dress that was purchased from the Golden Hour, a vintage shop in San Francisco. The night before, I did a pinwheel wet set (typical in the 1940s) on my hair and went to bed in a scarf wrapped around my head. The next morning I was transformed into Josephine. I woke up, combed out my hair, and styled it. I picked out my dress from two options. I applied a Victory Red lipstick by Besame cosmetics, a company that takes inspiration from worn colors during certain eras. A color inspired this particular lipstick from 1941. I applied black wing for my eyeliner and colored in my brows. I choose to use a photo style reminiscent of a black and white photo that added color. I wanted this photo to look like a portrait that would be autographed and given to fans of Josephine Bustamante."

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Sydney Wagman is a freshman at San Francisco State University. She wrote this piece for her English 105 course with Professor Michael Coyne. When Professor Coyne assigned a personal narrative based on global events, Wagman knew she would talk about her grandma. Wagman’s grandma valued the beauty in whatever life had to offer, a value Wagman herself held onto deeply as she watched her grandma battle cancer amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. |

Sydney Wagman

White Butterflies

In Memory of Grandma Diana Velez

White Butterflies

In Memory of Grandma Diana Velez

Sometimes fragments of my life feel like a movie, although movies aren’t always directed to be perfect or pretty. At difficult times, I latched onto the hope that my film’s director would shout “CUT," but I know now that he doesn’t work that way. I learned this when my grandma was diagnosed with Stage 3 cancer.

Eternity, by Calvin Klein, was a good indicator that I was at Grandma’s place. The scent was soaked throughout her dark and elegant clothes. It was her signature, along with Revlon lipstick kisses that left a garnet stamp on my pale skin-- a complexion she always insisted on complimenting.

“Mija, you have the skin of a porcelain dolly!”

Our sleepovers were the most meaningful. As the moon replaced the sun, we stuck to our sacred ritual. Saltine crackers and Diet Coke fueled endless hours of conversation. Together we laid side by side in a room that constantly ran hot, for a grandma who was always cold. As cracker crumbs lined our pillows, these nights contained moments when the best advice was given. Although I should pass her advice along, it was oftentimes uncensored for my ears only.

Rounded bubble-lettered balloons crinkled upon my dewy front lawn, announcing the year of my graduation. Busy with scholarships, final applications, and high school graduation around the corner, two months had passed since I had last seen my best friend. Prior to her diagnosis, my grandma made it apparent that she feared medical checkups, and with good reason. Her fear of doctor visits did not stem from superstition, despite her core beliefs that seeing owls or removing the emerald ring wrapped around her finger was bad luck. Growing up alongside five siblings, all but one passed away due to illnesses, and cancer was the cause of death for most. Her fear of doctor appointments caused her to make stubborn remarks as my family persisted in trying to get her to go to one. She always made sure her statements were comical when serious subjects arose:

“Shit, I’m not going to see a doctor, I am perfectly fine. I just need a Coke.”

I missed when she could refuse her doctor visits.

With the small window of time she had left before being hooked to an IV, she would call me. She sounded drastically different each time. While battling for the strength to overcome cancer, she still put my well-being first. Oftentimes, she would veil her pain by distracting me with constant reminders of how much she loved and missed me.

“I love you and I’ll talk to you soon, I’m just tired Mija.”

I would play my part in lifting her spirits. I kept her up to date with the latest news, but trying to find positive stories amidst a pandemic was challenging. I know it isn’t orthodox to ask for favors in prayer, but still I tried simply asking that she would get better. One day, I began seeing a single white butterfly flutter by my side. Then another one the day after that, and so on. I told my grandma about each encounter and painted her a large mural to brighten up her hospital confinements. The canvas showed a willow tree swaying in a field of flowers as butterflies peeked through the tall grass.

Eternity, by Calvin Klein, was a good indicator that I was at Grandma’s place. The scent was soaked throughout her dark and elegant clothes. It was her signature, along with Revlon lipstick kisses that left a garnet stamp on my pale skin-- a complexion she always insisted on complimenting.

“Mija, you have the skin of a porcelain dolly!”

Our sleepovers were the most meaningful. As the moon replaced the sun, we stuck to our sacred ritual. Saltine crackers and Diet Coke fueled endless hours of conversation. Together we laid side by side in a room that constantly ran hot, for a grandma who was always cold. As cracker crumbs lined our pillows, these nights contained moments when the best advice was given. Although I should pass her advice along, it was oftentimes uncensored for my ears only.

Rounded bubble-lettered balloons crinkled upon my dewy front lawn, announcing the year of my graduation. Busy with scholarships, final applications, and high school graduation around the corner, two months had passed since I had last seen my best friend. Prior to her diagnosis, my grandma made it apparent that she feared medical checkups, and with good reason. Her fear of doctor visits did not stem from superstition, despite her core beliefs that seeing owls or removing the emerald ring wrapped around her finger was bad luck. Growing up alongside five siblings, all but one passed away due to illnesses, and cancer was the cause of death for most. Her fear of doctor appointments caused her to make stubborn remarks as my family persisted in trying to get her to go to one. She always made sure her statements were comical when serious subjects arose:

“Shit, I’m not going to see a doctor, I am perfectly fine. I just need a Coke.”

I missed when she could refuse her doctor visits.

With the small window of time she had left before being hooked to an IV, she would call me. She sounded drastically different each time. While battling for the strength to overcome cancer, she still put my well-being first. Oftentimes, she would veil her pain by distracting me with constant reminders of how much she loved and missed me.

“I love you and I’ll talk to you soon, I’m just tired Mija.”

I would play my part in lifting her spirits. I kept her up to date with the latest news, but trying to find positive stories amidst a pandemic was challenging. I know it isn’t orthodox to ask for favors in prayer, but still I tried simply asking that she would get better. One day, I began seeing a single white butterfly flutter by my side. Then another one the day after that, and so on. I told my grandma about each encounter and painted her a large mural to brighten up her hospital confinements. The canvas showed a willow tree swaying in a field of flowers as butterflies peeked through the tall grass.

In the days following my grandma’s passing, white butterflies in numbers I couldn’t fathom danced around me.

I was finally able to visit her one afternoon. How our conversations changed so rapidly.

"This is my Tesla port Sydney, see." She pulled down the right side of her sweater to reveal a port for chemotherapy underneath her collar bone. I smiled at her jokes but excused myself to go to the bathroom moments after. I cried silently.

Month after month, COVID regulations became tighter. More restricting. I couldn’t visit my best friend in the hospital anymore and that killed me.

It was yet another restless night. My phone screen read 5 AM. The morning was silent, the birds didn’t sing, and gray clouds blanketed the sky. The loud silence was broken when I heard footsteps rushing along the tile floor. Making a distinction of sound, I knew they could only belong to my mom. After a tear-filled phone call, she was getting ready to leave the house and I ran into the garage quickly enough to go with her.

The time had come to say final goodbyes.

My mom acknowledged that my grandma didn’t look the same as the last time I saw her. It would have been far easier for her to say things happened too suddenly for me to have said goodbye, but I decided to go anyway. Comforting my mom while she was driving was one of the hardest things I had to do. Her words were shaky and tears drew as she repeated her frustration.

“Sydney— she only wanted a Pepsi. You know how she likes Coke, but during my last visit to her, all she wanted was a Pepsi. I ran to the vending machine. But Sydney, they didn’t have it. They didn’t have her Pepsi. They didn’t have a single fucking Pepsi. I— I couldn’t get her a Pepsi, it’s all she wanted. I went to buy one but they didn’t allow me to bring it back to her.”

“Mom, it's okay. She loves you, it was only a Pepsi, it’s okay Mom. It’s okay.”

That’s the thing about COVID. It unforgivingly changed our lives in the smallest and largest ways. Something as small as bringing my grandma a Pepsi wasn’t possible, as no outside drinks were allowed within the hospital during the pandemic. Among other constricting rules, only four people were allowed in the hospital room to say goodbye. I took my cousin's name tag after she retrieved me from the lobby and snuck in, pretending I was her.

On October 20th of 2020, I told my best friend that I loved her for the last time.

She didn’t like being cold. I wanted to comb her hair and put on her favorite lipstick. I wanted to do all of the things she loved to do for herself, even though the list was small. I have since erased the memory of her appearance in that cold hospital bed. In those final glances I took, my grandma didn’t look like herself. Cancer tends to do that. Being as stubborn as she was, she waited until the very moment my mom and aunts had briefly left the room to end her pain. Never had I known someone to put others before themselves so instinctively. My grandma made this gift visibly transparent. The Pepsi my mom got her sat in our fridge for months after her passing. I stared at it for hours sometimes. I’m not sure why.

In May, I graduated with my grandma; her photo in a heart-shaped locket on my graduation cap. I am eager for the moment when she can walk alongside me again during graduation, only this time from San Francisco State University.

The pandemic changed my life in every way imaginable; it took away so much. Yet, despite all that was taken, there was beauty to be found. Remember how I said my life is like a movie? Even sorrowful films have their scenes of lightheartedness if you watch them closely enough. In the days following my grandma’s passing, white butterflies, in numbers I couldn’t fathom, danced around me. Fluttering in such close proximity, they looked ready to land on the palms of my hands as I reached out to them. A few circled my head as if they were tracing the curve of a halo. It was their wings combined that showed enough strength to compose that of an angel’s. My grandma embodied an angel. I took this visual masterpiece as a message that Diana Velez gained her second pair of wings. I’m forever grateful that I don’t hold the power to say “cut” in my movie because if I had such power, seeing white butterflies wouldn’t be half as special.

Reflections on Career Pathways

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Ev Guzman is a first-year college student majoring in English with a concentration in Creative Writing. They wrote this piece for Professor Jason Jackl’s English 114 class in Fall 2021 as a way to tell their story of finding themselves freely. They moved to San Francisco for college and to grow as a person. |

Ev Guzman

Finally I'm Running Towards Myself, Not Away

Finally I'm Running Towards Myself, Not Away

I never ran away from home, not once. I never did that thing kids do where they claim they hate their parents and then run down the street, only to come back crying an hour later. I did run from a lot of other things though. I spent most of my life trying not to make decisions and refusing to settle on one thing because I was scared of making the wrong choice. I claimed to have wanted to be multiple things when I was younger: a lawyer, a florist, a mathematician, and even a therapist. I ran away from myself and refused to accept who I was. Now, studying English at San Francisco State University, I feel as if I am finally starting to run towards my true self.

My whole life, no matter the age or time, I can only remember myself running. Not literally, but metaphorically. I don’t remember much from my childhood, but I do remember that my parents fought a lot. These were the first moments I remember running away. I would go to my room, as I was told, and immediately, as if it were second nature, grab the nearest library book. The words on the pages, and the characters in the stories, comforted me in a way no one or nothing else could; everything would fade away. Thinking back, it was here that I first fell in love with reading. Throughout elementary and middle school, I continued using reading as a form of escapism. I never wanted to be in my reality; I ran away to fictional worlds.

My whole life, no matter the age or time, I can only remember myself running. Not literally, but metaphorically. I don’t remember much from my childhood, but I do remember that my parents fought a lot. These were the first moments I remember running away. I would go to my room, as I was told, and immediately, as if it were second nature, grab the nearest library book. The words on the pages, and the characters in the stories, comforted me in a way no one or nothing else could; everything would fade away. Thinking back, it was here that I first fell in love with reading. Throughout elementary and middle school, I continued using reading as a form of escapism. I never wanted to be in my reality; I ran away to fictional worlds.

The words on the pages, and the characters in the stories, comforted me in a way no one or nothing else could; everything would fade away.

In the sixth grade, I began writing my own short stories. It was a way to sort out my thoughts and worries. Around middle school, I realized that I am gay. These stories helped me to express and explore the different parts of myself. This time was very hard for me as my mother’s homophobia meant I lacked the support system I desperately needed when first coming out. Because I did not have a good support system at home, my mental health took a turn for the worse. The only way I can describe high school is by saying that it was like I was on autopilot. I took the classes my counselor told me to, including AP and honor courses. I didn’t find myself truly enjoying any of my classes except for English. I always genuinely looked forward to English class; it was my escape. By the time my senior year came around, I knew that whatever career path I chose, I wouldn’t mind as long as it had something to do with English.

Going into college, I already knew I wanted to major in English. I was unsure how I would use my English degree post-graduation until I had the amazing opportunity to interview Lee Chen-Weinstein, a First-year Composition professor at San Francisco State University. Although I didn’t take one of Professor Chen-Weinstein’s courses, this was the first time I saw a non-cis-heteronormative professor, and I decided to ask them to interview for an English assignment. I asked, “How did you know you wanted to pursue a career in the field you are currently working in?” They explained how they did not know they wanted to teach writing until they found poetry written by queer authors and people of color: “The experience of being seen in poetry was a powerful one.” This inspired me to want to help people feel seen, to show people that literature has much to offer, and how sometimes we can see ourselves in the works of others. I also asked them, “What are some struggles that you faced throughout your career and getting to where you are now?” Their answer to this question gave me insight into what I could expect in the future if I were to pursue teaching. They told me that it was difficult to find work as a college instructor and how difficult it is to break the mold of, “the archaic systems in place in high education.” They also mentioned that they, “struggled with coming out as a trans and nonbinary person in a largely cis-heteronormative workplace.” This was by far one of the most valuable insights they could have given me, as a nonbinary person myself. While I know that most fields will be cis-heteronormative, it is encouraging to see such visible representation.

I also was able to interview Kathleen DeGuzman, an author and professor here at SFSU. This was another professor whose course I did not take; however, it was another instance where I felt seen as a person of color who is in the English program. Our conversation gave me additional insight into what my future in higher education could look like. I started by asking, “How did you know you wanted to pursue a career in the field you currently are working in?” She recalled how she spent a semester in London during college. It was here that her interest in the field of postcolonial studies was initially sparked, allowing her to be where she is now. She briefly mentioned how she had always loved literature and knew she wanted to major in English; this reassures me about my path as I feel confident in my passion for literature. I asked Professor DeGuzman, “Was teaching your first career choice? Did you consider other career paths?” She said that being a professor was her first career choice, but that she also wanted to be a filmmaker when she was younger. She said, “Even now, I write about film in my scholarly work… I’ve come to see my roles as an educator and as a scholar as practices of storytelling.” I hope that if I do end up teaching, I too can see my work as storytelling. Like Professor DeGuzman, I aspire to pursue what I love and incorporate other interests into my scholarly pursuits.

With the help of the interviews, I was able to get a better understanding of what I want and what I can expect for my future. My ideal self would be someone who is openly themselves; someone who has stopped hiding and running as they learned to truly love themselves. My ideal self is doing something they love. I want to become an English teacher of some sort, whether that be in high school or a college professor, I am not sure yet. I want to teach and I want to help people experience the comfort I do when reading or writing. I predict that I will be teaching in the future and that I will be happy in my career. I will be with someone I truly love, someone who accepts me for who I am. I will have cut out the people who do not support me or my identity and be surrounded by those who do. A lot of this contrasts with my “ought self,” the person people expect and want me to be. My ought self would have gotten a degree in psychology or sociology. My ought self would be working in a corporation that pays well and has good benefits. I wouldn’t be very happy as my ought self; if I was my ought self I would be the person my mom wants me to be. I would be straight and cisgender and I wouldn’t be disconnected from my family. I would feel trapped if I was my ought self.

I want to be happy. I want to do what I like, rather than what other people tell me to do. I have spent so much of my life running from everything and I am tired of it. I want to run towards myself. I want to run towards my future and not away from it. To do so, I have to run away from the doubts that keep me behind. I am eager for my future, though it is still unclear what exactly it will look like. All that matters is that I am moving forward. I am only able to move forward now because I am here, studying English at San Francisco State University.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Yvone Perez is finishing their fourth year at SFSU. They wrote this paper for English 216 with Professor Caroline Casper. The assignment asked students to connect a defining moment in their life with an animal. The inspiration for their paper stems from their college experience and the lessons it taught them.

Yvone Perez is finishing their fourth year at SFSU. They wrote this paper for English 216 with Professor Caroline Casper. The assignment asked students to connect a defining moment in their life with an animal. The inspiration for their paper stems from their college experience and the lessons it taught them.

Yvone Perez

The Dangerous Comfort Zone

The Dangerous Comfort Zone

I have had a fascination with chameleons ever since my parents took me to the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park and I watched the creatures blend perfectly into their environments. Though I was just a young girl, I remember feeling envious of their ability to protect themselves by changing the color of their bodies. I did not know it then, but I would be mirroring this self-protection ability on my own in a number of different ways later in my life.

The first time I consciously remember changing myself for protection was in college during the recruitment process of joining a sorority. This was my first mistake in college. I was trying to be like every other girl who seemed popular. I was convinced that if I dressed, spoke, and associated with certain fraternities, I would find happiness at my new school. I never thought that I would become one of the statistics we often hear about in the news, but becoming a statistic would ultimately lead me to law school.

Being like a chameleon stripped me of my individuality. Changing the person I was, did not make me safer, as it so often does for chameleons. Nobody warned me that San Diego State University’s sorority recruitment was similar to that of Southern state colleges: grueling. The process forces so many women to forget who they were, just to be popular. The top sororities were not looking for individuality. They were looking to form a collective. A collective in which acceptance had everything to do with fitting into the mold—blonde hair and white skin with thousands of followers on Instagram.

I regret trying to fit their mold. I regret partying with the top fraternities and sororities, trying to get myself invited to exclusive events. I did not look like them. Although I am white-passing, I have dark features from my Mexican ancestors. I was the shortest one in my friend group, and I was the only one who was considered middle class. During SDSU’s Parent Weekend, my white friends’ parents would stay at the Hilton. My dad always chose Motel 6.

During my sophomore year, I was sexually assaulted. I was so inebriated that I do not remember the fraternity boy ever getting on top of me. If not for my best friend Mia accidentally walking into the room, I do not know if I would have snapped out of the non-consensual sex that was happening. When I saw the surprise on her face, I felt guilty and ashamed. Her face allowed me to stop what had already happened and wrap myself in a blanket.

The first time I consciously remember changing myself for protection was in college during the recruitment process of joining a sorority. This was my first mistake in college. I was trying to be like every other girl who seemed popular. I was convinced that if I dressed, spoke, and associated with certain fraternities, I would find happiness at my new school. I never thought that I would become one of the statistics we often hear about in the news, but becoming a statistic would ultimately lead me to law school.

Being like a chameleon stripped me of my individuality. Changing the person I was, did not make me safer, as it so often does for chameleons. Nobody warned me that San Diego State University’s sorority recruitment was similar to that of Southern state colleges: grueling. The process forces so many women to forget who they were, just to be popular. The top sororities were not looking for individuality. They were looking to form a collective. A collective in which acceptance had everything to do with fitting into the mold—blonde hair and white skin with thousands of followers on Instagram.

I regret trying to fit their mold. I regret partying with the top fraternities and sororities, trying to get myself invited to exclusive events. I did not look like them. Although I am white-passing, I have dark features from my Mexican ancestors. I was the shortest one in my friend group, and I was the only one who was considered middle class. During SDSU’s Parent Weekend, my white friends’ parents would stay at the Hilton. My dad always chose Motel 6.

During my sophomore year, I was sexually assaulted. I was so inebriated that I do not remember the fraternity boy ever getting on top of me. If not for my best friend Mia accidentally walking into the room, I do not know if I would have snapped out of the non-consensual sex that was happening. When I saw the surprise on her face, I felt guilty and ashamed. Her face allowed me to stop what had already happened and wrap myself in a blanket.

Eventually, the bruises disappeared and I thought, like a chameleon that is constantly changing itself for self-protection, that I could continue to pretend like everything was alright...

Women like Ruth Bader Ginsberg (RBG) have recently inspired me to educate myself on feminism and analyze women’s issues on a deeper level. I connect with her story because she said she initially did not go to law school for women’s rights, but for her own selfish reasons. She explained that she felt like she could do a lawyer's job better than how she saw them practicing law. I immediately connected to her statement because she was not always interested in women’s rights yet was interested in law. She did not act like a chameleon; she stood out from everyone. She graduated first in her class at Columbia law, became the first person on both Harvard and Columbia Law reviews, co-founded the first law journal on women’s rights, and co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU. Nothing about her accomplishments can truly be compared to another woman of her time.

After the assault, I tried to ignore what had happened. Eventually, the bruises disappeared and I thought, like a chameleon that is constantly changing itself for self-protection, that I could continue to pretend like everything was alright by acting like my friends, who were happy. However, two weeks later, I started crying in the shower and could not stop. I was surprised that the first person I told was someone I was not even close to. It was a housemate who was living with us, and I broke down in front of her while she was eating dinner. I said, “I am not okay.” I realized I just needed someone to listen to me at that moment.

I was scared nobody was going to believe me because I waited to say something and did not report the assault immediately. But I eventually told the school and the fraternity that the boy was a part of.

Before being sexually assaulted, I had little interest in educating myself on feminism. I went to Berkeley High School, a high school that is arguably one of the most vocal about liberal politics, including feminism, in the East Bay. However, I still was not interested in studying feminism on my own. I had never felt unsafe as a woman or a young girl in my household. I realized after my assault that the most inspirational people for me to follow were successful women in law like RBG. I did not know it at the time, but my interest in criminal law was beginning to grow. I found power and strength in educating myself about feminism through examples of women who created policy changes and were highly educated in the law.

During my research in deciding whether or not to report to law enforcement, I read the jury instruction for proving a sexual offender guilty and it left me feeling extremely disheartened. California Penal Code [CPC] § 261(a)(3) reads, “The defendant is not guilty of this crime if he actually and reasonably believed that the woman was capable of consenting to sexual intercourse, even if that belief was wrong” (CPC § 261(a)(3)).

So much of this criminal justice policy regarding sexual assault has an effect on me. I would like to go to law school, to become exceptionally successful, similar to RBG, and change policy to help survivors of sexual assault. Before being sexually assaulted, I created ideas for stable careers based on television shows, without having a real connection to the career choices I was interested in. Again, I was subconsciously imitating a chameleon based on the popular culture examples that I would see. But I now have a different perspective on life, given what happened to me in San Diego. I no longer want to be a chameleon for reasons like fitting in with a crowd that does not promote emotional growth for me. I have also educated myself more on feminists like RBG and have read books about feminism to further my emotional and intellectual growth.

My own self-realization has opened my eyes to being emotionally aware that it is okay to want to protect myself by acting like a chameleon at times. Although I have stopped changing the person I am to appease others and give importance to irrelevant ideas like popularity, I know now that it is a survival tactic. I cannot be too critical of myself for simply wanting to protect myself. However, I also recognize that protecting myself in dangerous situations is different than trying to fit in. It feels safe to be in my comfort zone, but I will not emotionally grow there. I am done trying to mirror the colors of others; I am finally willing to accept my own.

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Nyla Raffety-Williams is a first-year Africana Studies major. She wrote this piece for “Writing the First Year: Finding Your Voice,” taught by Professor Justin Robinson. In this piece, Raffety-Williams explores experiences that influenced her racial identity development and how this motivated her to embark on a journey for justice as a criminal justice attorney. |

Nyla Raffety-Williams

Experiences with Racial Identity Development

Experiences with Racial Identity Development

The first thing I remember is being too small—a mere six-year-old with no understanding of death or loss, too small to even attend his funeral. I was too small to understand why my mom was screaming over the phone and why my grandma wept as she sat in front of the TV. The headline “Black man shot dead by BART Police” was in big bright letters on the news, and the video that became his legacy was on repeat on what seemed to be every channel. My grandma hugged me to her side, tucking my head in so I wouldn’t see what was on the screen. But I heard it: “I’m going to tase him,” a popping sound, the screams of bystanders, “You shot me.” On January 1, 2009, at 2:15 A.M. I lost my uncle to police brutality. It would take me five years to fully understand what happened that night and another three to begin implementing my plan to do something about it. I first had to educate myself, which started in high school when I joined the Race, Policy, and Law Academy at Oakland Tech. The murder of my uncle and the knowledge I gained from being a part of the RPL Academy at Oakland Tech is my motivation for embarking on my journey to achieve justice and a more equitable legal system for people of color, especially Black people.

My uncle was murdered because of a cop’s carelessness and ignorance about his skin color; it was from losing him that I learned skin color matters. Although I was able to assimilate to some degree, I was always treated differently because I was the only Black person in my neighborhood and elementary school. It wasn’t until my uncle’s murder that I understood why my teachers and peers would bully me. Why I was always singled out for scolding and punishments. Why my teacher allowed another student to punch me in the stomach and not say anything about it until my mom discovered the bruise. It was because I was Black; I was an other. The one and only in that community. I spent the rest of my time at that school reserved and consumed by self-loathing. I had been programmed to be ashamed of myself and my Blackness, but my environment shifted when I got to middle school. Everyone was like me, all students of color and I finally felt like I belonged. I went from being the one and only to being one of many.

My uncle was murdered because of a cop’s carelessness and ignorance about his skin color; it was from losing him that I learned skin color matters. Although I was able to assimilate to some degree, I was always treated differently because I was the only Black person in my neighborhood and elementary school. It wasn’t until my uncle’s murder that I understood why my teachers and peers would bully me. Why I was always singled out for scolding and punishments. Why my teacher allowed another student to punch me in the stomach and not say anything about it until my mom discovered the bruise. It was because I was Black; I was an other. The one and only in that community. I spent the rest of my time at that school reserved and consumed by self-loathing. I had been programmed to be ashamed of myself and my Blackness, but my environment shifted when I got to middle school. Everyone was like me, all students of color and I finally felt like I belonged. I went from being the one and only to being one of many.

At this middle school, I was introduced to much more positive narratives about my Blackness; they greatly contrasted the ones I had been force-fed in the past. I was motivated to accept the fact that I could not only graduate high school but also go to and graduate college. I began to learn more authentically about my culture and accept and love my culture as a part of me. However, while I was learning to accept myself, more people were being murdered by police officers for being themselves. People like Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice were murdered like my uncle. I became consumed by outrage and grief for the lives lost; I had an overwhelming desire to do something, but I wasn’t yet sure of what I could do. What could I expect to do as a mere 11-year-old? I was still too small.

I began to learn more authentically about my culture and accept and love my culture as a

part of me.

The anger and outrage remained, but the hopelessness I felt faded in high school. There, I became aware of the power I had and began making decisions that seemed insignificant at the time but inspired me to take my first steps towards making a change. In a moment of rebellion against my family, I applied for the Race, Policy, and Law Academy (RPL) at Oakland Tech instead of the Engineering Academy. I had doubts that I would even be accepted to the academy since I was originally waitlisted for Oakland Tech. However, I was indeed accepted, and I’m glad that I was. In the beginning, I was not sure what the relevance of this academy would entail in terms of courses, but as I went along, I began to better understand and grow passionate about the issues we discussed. My first course in this academy examined how the law in all its forms mistreats and discriminates against minorities, and has done so historically. I began to understand better what needed to be done for proper justice to be achieved. More people of color had been murdered, and this horrific trend of police brutality showed no signs of ceasing. RPL provided me with the knowledge and opportunities that would allow me to make a change. It was during my time at RPL that I attended my first protest against police brutality. It occurred in response to the murder of Stephon Clark; at this protest, I became aware of the power my voice held. Being in RPL encouraged me to be vocal about injustice and it was here I decided to be a lawyer.

I’m in college now with everything I learned about policy, the legal system, and racism from RPL. I’m studying as an Africana Studies major and planning to double in Psychology later down the line. My knowledge and the pain of losing my uncle serve as my motivation. I’m going to continue to work towards my dream of being a Criminal Justice Attorney to diversify the legal field and make sure that people of color, especially Black people, are never made to fall victim to the system again. I’m no longer too small, and I’m eager for my journey for justice to continue.

|

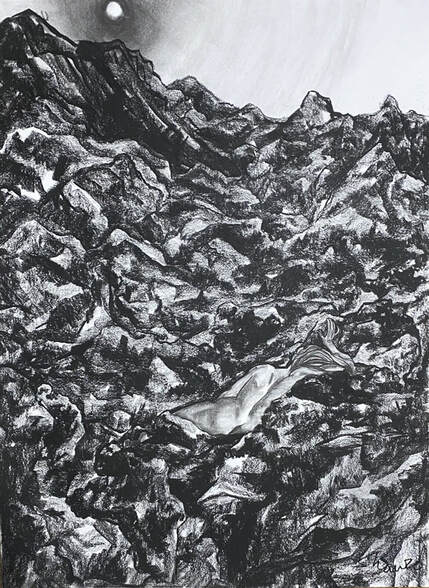

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Breanna Barton-Shaw is a junior at SFSU, transferring in from Los Angeles City College after receiving her associates degree in English. This collection of work was created for a community college class in 2021. Currently in the Comparative and World Literature department, she is a lifetime art hobbyist and delivers artwork during the furies of frustration and anxiety from current events. She works in charcoal and symbolism, inspired by Käthe Kollwitz. |

Investigative Pieces

Mayer Adelberg

Exploring the Intersection of Musicology, Sustainability, and Preservationism

Exploring the Intersection of Musicology, Sustainability, and Preservationism

Introduction

In 1970, Peter Matthiessen wrote, “Out here on the flat Valley floor there is nothing left of nature; even the mountains have retreated, east and west” (Wald). That same year, Joni Mitchell came out with her song “Big Yellow Taxi;” in it, she mentions the issue that Rachel Carson writes of in Silent Spring and what Matthiessen was so concerned about: the toxic and destructive pesticides that plague the Central Valley and beyond.

Forty-two years later, in his book Ecomusicology: Rock, Folk, and the Environment, anthropologist Mark Pedelty asks, “How might music actually promote and inspire the sort of collective action needed to make our towns, cities, and nations more sustainable?” (Pedelty). In his work, he looked at multiple pieces of so-called environmental music, or music that helps or harms the environment. In this paper, I will amalgamate the implications of ecology, sustainability, preservationism, toxicity, and social action, and the impact music has on all of these topics and more.

Background

Joni Mitchell’s 1970 hit “Big Yellow Taxi” came to her during a vacation in Hawaii. In a Los Angeles Times interview with Robert Hillburn entitled “Both Sides, Later,” she recalled that from her hotel window she “saw...beautiful green mountains in the distance,” looked down, and saw “a parking lot as far as the eye could see” (Hillburn). The song criticizes anthropocentric environmental ideology and profiting from environmental hoarding or destruction. Mitchell’s archived website defines some of the lyrics that may be more ambiguous to some listeners, especially those unfamiliar with Hawaii. The “pink hotel,” for instance, refers to the Royal Hawaiian in Honolulu, and the “tree museum” she describes is the Foster Botanical Garden, a museum that despite protecting and maintaining “native Hawaiian flora and endangered species” charges visitors a five-dollar admission fee. Mitchell writes about all the ways in which preservationism was not a priority in 1970s Hawaii (the efforts were directed at tourism) even the mainland United States, apparent in her criticism of the carcinogenic pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, an agricultural insecticide until the United States banned its use in 1972. Overall, and to this day, the bulk of “Big Yellow Taxi” is a critique on then-common environmental practices.

In between this critique, or perhaps lying on top of it, is Mitchell’s famous lyric about the realities of paving over paradise to “put up a parking lot.” This phrase, now an anthem for environmentalists and ubiquitous in environmental rhetoric, appears in dozens of journal articles and research papers and has appeared in essentially every cover of the song despite other profound lyrical changes. The lyric, appearing and reappearing nine times in a song only two minutes and sixteen seconds long, most importantly emphasizes and communicates preservationism and conservationism in not only its historical definition of “leaving the environment in a better state than the condition he or she found it” but also in its dominant and most contemporary sense, where “viewing humankind as an inherently intrusive interloper upon nature” (Harding).

Analytical Method

As recommended by Sonja Foss in her text Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice, I approached ideological analysis by first identifying the elements of my artifact, in this case, Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi:” paradise, trees, money, the birds and the bees, hotels, and hotspots. In identifying associations with these elements, I recognized inanimate and animate versions of living and non-living beings, protection, destruction, and toxicity. Formulating ideas out of these associations, I thought of the environment, human nature, ecology, air quality, breathing, walking barefoot, listening to nature without interference, and music. Finally, constructing ideologies from these ideas, I thought of preservationism and sustainability. This method was excellent for understanding how to transition from elemental items to ideologies.

Research Question

How does a song communicate preservationism and sustainability?

Report of Findings

Music, sustainability, and preservationism are three unique but intertwined facets of ecology. One could consider music as a means of listening to the environment. Others may consider the origins of musical instruments and their ties to native Brazilian Pernambuco wood (Titon). Some may be reminded of pieces of music that tie us directly to the world outside, such as Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons; many more might think of music and ecology as being tied together only when songs specifically mention the environment.

To consider the intersection of songs, preservationism, and sustainability, I believe it is only fair to begin with the natural world and the sources of how we make and play music. This, as Jeff Titon puts it in his book Toward a Sound Ecology: New and Selected Essays, considers “music’s direct impact on the environment” (Titon). After all, the communication of music likely begins before music is created—this originates in sources of materials and wealth—and is mostly composed of trees. Trees, as Mitchell alludes to, are elements of the natural world that have occasionally been hidden from the public for a fee. As described in the introduction, one lyric in “Big Yellow Taxi” refers to the Foster Botanical Garden. Peter Crane, in his 2013 book Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot, notes how this type of preservation and conservation, known as ex situ conservation, “is a key tool to preserve plant diversity for the long term” but falls short because it “cannot preserve the processes that maintain species in their natural habitat, nor can it sustain the ecological services provided by the community of which the species is part” (Crane). Ex situ conservation still potentially removes native flora from its natural habitat—in reality, so does using trees for musical instruments. In our current digital stage, it is possible to distance music from the environment, but truly only electronic music succeeds in this futile task. Guitars, pianos, bassoons, clarinets, and percussive instruments are sourced from around the world, sometimes removing the culture from the music. In contrast, when the Chopi of Mozambique created a xylophone in the presence of English ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey, Tracey emphasizes in a journal article entitled “Wood Music of the Chopi” how, “all the materials used in the making of this instrument, such as various woods, beeswax, palm-leaf string and resonators of hard shelled fruits, were collected within a few miles of the makers' village” (Tracey). However, it is sometimes arguably acceptable for music to communicate ecology when the materials are respected by the creators, even if the origins are different from the destination. For instance, in describing their soundboard, the esteemed piano company Steinway & Sons writes that Sitka spruce is “the most resonant wood available.” This spruce, combined with “the rigidity of hard rock maple,” creates the foundation for the “instrument’s superior tone” (Steinway & Sons, n.d.). (As an aside, my immediate family owns a 1954 Steinway & Sons that has been passed down through three generations. In comparison with today's Yamaha or Kawai pianos, simply looking at the wood of a Steinway makes one understand the complexity and care required to build one. Playing it is an entirely different, surreal experience.) From start to finish, it takes over one year to create a Steinway & Sons piano (Bambarger), and despite the removal of wood from nature to form the piano, the emotion conveyed through the quality and the player often signifies so much more than chopping down a chair; through craftsmanship, the quality and relatively local sources of the wood, and the artisanship that is required to construct it, nature, quite subjectively, flows freely through the music. It is through this sort of skilled creation that allows music to be interpreted as one with the music as opposed to a separate entity. Consequently, preservation is, at least in part, communicated by the music that emerges from fine instrumentation.

In 1970, Peter Matthiessen wrote, “Out here on the flat Valley floor there is nothing left of nature; even the mountains have retreated, east and west” (Wald). That same year, Joni Mitchell came out with her song “Big Yellow Taxi;” in it, she mentions the issue that Rachel Carson writes of in Silent Spring and what Matthiessen was so concerned about: the toxic and destructive pesticides that plague the Central Valley and beyond.

Forty-two years later, in his book Ecomusicology: Rock, Folk, and the Environment, anthropologist Mark Pedelty asks, “How might music actually promote and inspire the sort of collective action needed to make our towns, cities, and nations more sustainable?” (Pedelty). In his work, he looked at multiple pieces of so-called environmental music, or music that helps or harms the environment. In this paper, I will amalgamate the implications of ecology, sustainability, preservationism, toxicity, and social action, and the impact music has on all of these topics and more.

Background

Joni Mitchell’s 1970 hit “Big Yellow Taxi” came to her during a vacation in Hawaii. In a Los Angeles Times interview with Robert Hillburn entitled “Both Sides, Later,” she recalled that from her hotel window she “saw...beautiful green mountains in the distance,” looked down, and saw “a parking lot as far as the eye could see” (Hillburn). The song criticizes anthropocentric environmental ideology and profiting from environmental hoarding or destruction. Mitchell’s archived website defines some of the lyrics that may be more ambiguous to some listeners, especially those unfamiliar with Hawaii. The “pink hotel,” for instance, refers to the Royal Hawaiian in Honolulu, and the “tree museum” she describes is the Foster Botanical Garden, a museum that despite protecting and maintaining “native Hawaiian flora and endangered species” charges visitors a five-dollar admission fee. Mitchell writes about all the ways in which preservationism was not a priority in 1970s Hawaii (the efforts were directed at tourism) even the mainland United States, apparent in her criticism of the carcinogenic pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, an agricultural insecticide until the United States banned its use in 1972. Overall, and to this day, the bulk of “Big Yellow Taxi” is a critique on then-common environmental practices.

In between this critique, or perhaps lying on top of it, is Mitchell’s famous lyric about the realities of paving over paradise to “put up a parking lot.” This phrase, now an anthem for environmentalists and ubiquitous in environmental rhetoric, appears in dozens of journal articles and research papers and has appeared in essentially every cover of the song despite other profound lyrical changes. The lyric, appearing and reappearing nine times in a song only two minutes and sixteen seconds long, most importantly emphasizes and communicates preservationism and conservationism in not only its historical definition of “leaving the environment in a better state than the condition he or she found it” but also in its dominant and most contemporary sense, where “viewing humankind as an inherently intrusive interloper upon nature” (Harding).

Analytical Method

As recommended by Sonja Foss in her text Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice, I approached ideological analysis by first identifying the elements of my artifact, in this case, Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi:” paradise, trees, money, the birds and the bees, hotels, and hotspots. In identifying associations with these elements, I recognized inanimate and animate versions of living and non-living beings, protection, destruction, and toxicity. Formulating ideas out of these associations, I thought of the environment, human nature, ecology, air quality, breathing, walking barefoot, listening to nature without interference, and music. Finally, constructing ideologies from these ideas, I thought of preservationism and sustainability. This method was excellent for understanding how to transition from elemental items to ideologies.

Research Question

How does a song communicate preservationism and sustainability?

Report of Findings

Music, sustainability, and preservationism are three unique but intertwined facets of ecology. One could consider music as a means of listening to the environment. Others may consider the origins of musical instruments and their ties to native Brazilian Pernambuco wood (Titon). Some may be reminded of pieces of music that tie us directly to the world outside, such as Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons; many more might think of music and ecology as being tied together only when songs specifically mention the environment.

To consider the intersection of songs, preservationism, and sustainability, I believe it is only fair to begin with the natural world and the sources of how we make and play music. This, as Jeff Titon puts it in his book Toward a Sound Ecology: New and Selected Essays, considers “music’s direct impact on the environment” (Titon). After all, the communication of music likely begins before music is created—this originates in sources of materials and wealth—and is mostly composed of trees. Trees, as Mitchell alludes to, are elements of the natural world that have occasionally been hidden from the public for a fee. As described in the introduction, one lyric in “Big Yellow Taxi” refers to the Foster Botanical Garden. Peter Crane, in his 2013 book Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot, notes how this type of preservation and conservation, known as ex situ conservation, “is a key tool to preserve plant diversity for the long term” but falls short because it “cannot preserve the processes that maintain species in their natural habitat, nor can it sustain the ecological services provided by the community of which the species is part” (Crane). Ex situ conservation still potentially removes native flora from its natural habitat—in reality, so does using trees for musical instruments. In our current digital stage, it is possible to distance music from the environment, but truly only electronic music succeeds in this futile task. Guitars, pianos, bassoons, clarinets, and percussive instruments are sourced from around the world, sometimes removing the culture from the music. In contrast, when the Chopi of Mozambique created a xylophone in the presence of English ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey, Tracey emphasizes in a journal article entitled “Wood Music of the Chopi” how, “all the materials used in the making of this instrument, such as various woods, beeswax, palm-leaf string and resonators of hard shelled fruits, were collected within a few miles of the makers' village” (Tracey). However, it is sometimes arguably acceptable for music to communicate ecology when the materials are respected by the creators, even if the origins are different from the destination. For instance, in describing their soundboard, the esteemed piano company Steinway & Sons writes that Sitka spruce is “the most resonant wood available.” This spruce, combined with “the rigidity of hard rock maple,” creates the foundation for the “instrument’s superior tone” (Steinway & Sons, n.d.). (As an aside, my immediate family owns a 1954 Steinway & Sons that has been passed down through three generations. In comparison with today's Yamaha or Kawai pianos, simply looking at the wood of a Steinway makes one understand the complexity and care required to build one. Playing it is an entirely different, surreal experience.) From start to finish, it takes over one year to create a Steinway & Sons piano (Bambarger), and despite the removal of wood from nature to form the piano, the emotion conveyed through the quality and the player often signifies so much more than chopping down a chair; through craftsmanship, the quality and relatively local sources of the wood, and the artisanship that is required to construct it, nature, quite subjectively, flows freely through the music. It is through this sort of skilled creation that allows music to be interpreted as one with the music as opposed to a separate entity. Consequently, preservation is, at least in part, communicated by the music that emerges from fine instrumentation.

This is the music of the forest, and it is vast and wide and ever-changing and everlasting—much like nature itself.

Beyond their ability to convey meaning simply through instrumentation, songs and music can also inspire action. During the process of writing his book, Pedelty and an analyst conducted research about music fan blogs, more specifically activists, about “their musical interests and motivations” (Pedelty). He noted, “surprisingly,” that “72% of the activists” drew “important information from songs” (Pedelty). This information likely influenced their understanding of the natural world and provided a new perspective, which may be why “a 23-year old stated that … Big Yellow Taxi … inspired her to ‘work towards having a more sustainable campus’” and also may be why a “57-year-old explained that … Big Yellow Taxi” provided “inspiration during a struggle to keep development in Fremont, California from destroying 1,000 acres of local farmland” (Pedelty). Other songs that Pedelty heard were Neil Young’s After the Garden and Prairie Wind, Men They Couldn’t Hang’s Midnight Train, and even Woody Guthrie’s This Land is Your Land. Additionally, Pedelty writes how activists “think about global music, even when their activism is mainly local” (Pedelty). Although “few North American popular songs are explicitly about environmental issues” and “the same songs get cited over and over,” music conveys preservationism, activism, and ecological awareness simply by existing in the mainstream, regardless of its dominance (Pedelty).