SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition

(Please click on authors and headings under Contents to navigate through the document)

We are excited to present the second annual volume of Sutro Review: SF State Journal for Undergraduate Composition, an academic journal produced by graduate students devoted to publishing the work of undergraduate students at San Francisco State University.

Sutro Review celebrates the diverse and talented voices among undergraduates at SF State and aims to share those voices with the broader learning community. Our second issue includes nineteen student essays from a variety of class levels and disciplines, as well as showcases some of the teaching faculty who informed those good works. Essays include a rich palette of topics: a Russian novelist’s utilization of magical realism, the increasing threat of oceanic changes, how to embrace autism, Filipino colonial mentality… to name a few! In short, we provide a glimpse into the broad spectrum of work produced in a range of undergraduate courses at our university.

Special thanks goes to English Department Chair, Sugie Goen-Salter, Director of Composition, Tara Lockhart, and the SF State University Instructionally Related Activities Fund for making this project possible.

We hope you enjoy reading!

Sincerely,

Sutro Editors

Faculty Supervisor:

Christy Shick

Editors:

Kandace Lindstrom

Rene Juarez

FRESHMEN

Kaitlyn Kehrmeyer, “Ask Politely: the Gender Language Revolution”

Megan Martino, “Cultural Identity and Dining in ‘Fish Cheeks’

Jan Michaela Yee, “Down to a Trio”

Nimiksha Mahajan, “The Benefits of Bilingual Edudation”

Ivan Manriquez, Jr., “The Analytic Perspective of Ocean Changes”

SOPHOMORES

Swetha Pottam, “Her Body, But Not Her Choice”

Celine Margaret Wuu, “The Bay Area Urban Indian Community”

Alexa Almira, “Asians in the Library”

Christina Colombo, “The Last of the Yahi”

Andrew Harrington, “Climate Change: From Theory to Reality”

Jovana Toscano, “Neurotribes and Making Peace with Autism”

JUNIORS

Isaiah Dale, “The Oriflammes of Non-Opportunistic Individuals”

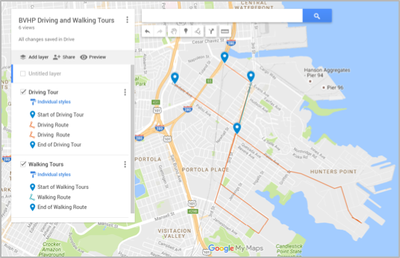

Jose Francisco, “Community Assessment: Bayview-Hunters Point”

Aureolus Stetzel, “Jamaica in Perpetual Crisis”

SENIORS

Kareena del Rosario, “The Power of the Fabliaux”

David Hlusak, “First Came the Sound”

Nancy Rodriguez Zambo, “Emancipating the Curated Filipino”

Emily Hollocks, “Tyrannical Dictatorships in Deathless”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PUBLICATION INFORMATION

Ask Politely: the Gender Language Revolution

Kaitlyn Kehrmeyer was born and raised in a small town in the foothills north of Los Angeles. Although much of her childhood was spent living in the suburbs and hiking/exploring the outdoors, she absolutely adores the vibrancy and culture of city life. Prior to her move to SF, her adolescent life was a youthful whirlwind. She spent the better half of her high school years attempting to balance her responsibilities as a student with the lures of the DIY music and art scene. By sophomore year of high school, she decided to ditch the name Kaitlyn and go by Kehrmie instead; she forged a sense of identity and character through that name (by which she still goes). Literature, poetry, music, and photography have allowed her to explore many different aspects of herself, as well as her role in the world. While she originally intended to study Environmental Science at SF State, she’s recently decided to pursue a her undergraduate degree in Sociology.

COMMENT FROM LECTURER, SARA FELDER:

In this essay, Kaitlyn (AKA Kehrmie) critiques our society for its frequent erasure of the experience of transgender and gender nonconforming people. Offering a seemingly simple solution -- the use of the pronoun “they”, Kehrmie’s sly linguistic revolution brings awareness to the experience of many people on the margins of social constructions of gender. I appreciate her clear voice and compelling investigation into how language informs culture and bias. She completed her essay for our research unit of English 114, after a couple of drafts and peer review. Students were asked to choose a topic in the intersection of language and social justice. Kehrmie’s essay arrives at an urgent moment as legal battles rage and society ponders the civil rights of transgender and gender nonconforming folks.

False precepts cause LGBTQ people to be victims of targeted acts of prejudiced hatred and violence. The New York Times reports that in America specifically, “L.G.B.T. people are [now] twice as likely to be targeted as African-Americans, and the rate of hate crimes against them has surpassed that of crimes against Jews” (The New York Times, 2016). Furthermore, with about 84% of LGBTQ youth reporting being bullied, and another 64% of LBGTQ youth admitting they feel unsafe in public schools, it is now imperative for all people to increase their education and awareness about the LGBTQ community (LGBT Bullying Statistics). To accomplish this, gender-neutral language must be incorporated into the media and mainstream society. This will educate people and help us progress towards a safer and more inclusive culture where all people feel safe, represented, and visible.

Gender identity does not exist within two implicitly defined categories of male and female; rather, it exists as a spectrum where any given person falls between different extremities of masculinity and femininity. Although people range variably on the spectrum, many do not entertain the idea of multiple gender identities because it challenges their schema of what gender and sexuality means in mass culture. Mainly, people tend to have difficulties referring to the androgynous or ambiguous nature non gender-binary individuals. A cisgender person is someone “whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex” (OED). And in turn, a non-cisgender (or non-gender binary) person can be defined as someone whose gender does not coincide with their biological sex (i.e. transgender, genderqueer). Although the LGBTQ community is composed primarily of people with different non-heterosexual identities (lesbian, gay, bisexual), alternative gender identities are also included in the community (transgender, genderqueer, non-gender binary etc). The term “community” itself is a general term to define the human connection, common culture, and support system shared by LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) people.

In our society, an individual’s ability to explain and understand gender is limited by our language. Mainstream culture currently lacks the proper language and pronouns to attach to other gender identities; so many people simply do not understand people who identify with non-binary gender, because there is no language to dignify it. A theory regarding the “bound[s]” and “restraints of language,” entitled the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, reflects this by stating “an individual's thoughts and actions are determined by the language [or languages] that individual speaks” (linguist.org). Moreover, the hypothesis states, “all human thoughts and actions are bound by the restraints of language” (linguistlist.org). This means that people can only recognize and understand things on a deeper level once they have the language and words to describe it. Therefore, by providing people with “they” (a gender neutral pronoun) and “ze”(a gender free pronoun), unaware cisgender and/or heterosexual people have a word that they can use to respectfully address and refer to transgender or gender queer individuals.

From a young age, children are taught to understand both concepts of male and female as being social norms. By the age of four, most children have already formed a “stable sense of their gender identity,” which is then reinforced by specific “learn[ed] gender role behavior[s]” (American Academy of Pediatrics). As time progresses, current generations age and new ones appear, with a blanket expectation of a cisgender identity and the idea that these learned gender role behaviors are socially normal and accepted as ‘right’ and ‘healthy’. Our current society tells children that they must act a specific way in order to reflect their sex and associated gender identity. But what happens when LGBTQ children are unaware that there is something outside of being a boy who “acts like a boy” or a girl who “acts like a girl? Those who fall outside cisgender vocabulary feel alienated and confused because there is no role model or institution telling them that being “different” is not unnatural or wrong. Seeing adults (in real life or the media) who identify outside social norms, or otherwise use inclusive and tolerant speech, would be enough to make non-cisgender kids feel validated and recognized. But sadly, with only about 4% of all major recurring characters on TV being lesbian, gay, or bisexual (and even fewer being transgender or genderqueer), representation of marginalized and minority populations in the media continues to be a pressing issue (GLAAD).

Due to the millennial generation’s upbringing in the information age, society is beginning to see more drastic expressions of previously taboo topics. Discussions of gender, sexuality, and sex are regularly “on the table,” so to speak. The hope is that new, reformed language habits will follow these newfound gender expressions; and we will no longer need to assume all people must be male or female. Rather than using “he” or “she” pronouns, replacing either with “they” as the default pronoun establishes a gender neutral social norm and limits the assumption of someone’s identity based on their physical appearance. Using “they/them” before “he/she” addresses all cisgender and LGBTQ people alike as one, instead of creating further illusions of separation in our already divided society. Using the same language for people of differing gender identities sets a precedent for tolerance and awareness, which will help LGBTQ individuals feel safer in their wider communities.

Non-cisgender people need to have their “identities affirmed by other[s]” as all people do, regardless of identity or background (Zimman). Correctly referring to someone through the use of their preferred gender pronoun validates their identity and plays a huge role in fighting back against hate crimes and violence that disproportionately affect the LGBTQ community. Changing your everyday speech affects violence because words can affirm the humanity of another person and preach awareness and tolerance toward different groups of people in society, thereby impacting hate crimes and discrimination.

The push for gender-neutral language and representation of LGBTQ people in the media cannot be achieved while others view the very existence of LGBTQ individuals as a radical protest against gender norms. People often do not recognize the cause for gender-neutral movements because they feel their personal politics are being challenged or offended. It is important to question preconceived ideas of gender and sexuality. We must insist people recognize non-cisgender individuals and use gender-neutral pronouns, even if it makes them uncomfortable or angry.

Despite political counterarguments, someone else’s identity has nothing to do with another person’s politics. Calling a person by their correct name or pronoun is respectful and affirms them as a real person, instead of framing them as an outsider by ignoring their personal preferences. So, instead of protesting the political correctness of gender-neutral language, one should turn their attention to the actual person whom they are addressing, because gay and queer issues are human issues. Beneath the language and politics, these are human beings who deserve human names. In a world where the murder of transgender people is at an all time historical high (Steinmetz), and where Donald Trump (campaigning on a largely xenophobic, misogynistic, sexist, racist platform) has become the president of the United States, there has never been a better time to talk about those less recognized. By using non-inclusive language, you are misgendering LGBTQ people, and thereby telling them they don’t matter and that their identity and feelings are not valid.

Altogether, for people in marginalized communities, the world is already a terrifying place to exist. I believe all people have a democratic right to exercise self-expression, and to feel safe doing so. I will not stay silent as long as another human is being threatened, harassed, or killed simply because they express themselves freely. Our society’s democracy should protect minorities, not diminish them, and incorporating gender-neutral language into society would address the issues of LGBTQ minorities directly. So next time you meet someone who may be different from you, be civil and neutral, or politely ask them how they identify. Once we begin to recognize the humanity behind any name or pronoun, we can start an amicable revolution.

"Ask A Linguist FAQ." Ask A Linguist FAQ: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Indiana University Department of Linguistics, n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

"cisgender, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2017. Web. 23 March 2017.

Darr, Brandon, and Tyler Kibbey. "Pronouns and Thoughts on Neutrality: Gender Concerns in Modern Grammar." Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee 7.1 (2016): n. pag. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, Apr. 2016. Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

"Gender Identity Development in Children." HealthyChildren.org. American Academy of Pediatrics, 21 Nov. 2015. Web. 01 Dec. 2016.

GenderqueerID. "Genderqueer History." Genderqueer History. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

"GLAAD - Where We Are on TV Report - 2015." GLAAD. N.p., 20 Jan. 2016. Web. 04 Dec. 2016.

"LGBT Bullying Statistics." No Bullying. N.p., 7 Nov. 2016. Web. 7 Nov. 2016.

Mykhyalyshyn, Haeyoun Park and Iaryna. "L.G.B.T. People Are More Likely to Be Targets of Hate Crimes Than Any Other Minority Group." The New York Times. 16 June 2016. Web. 4 Feb. 2017.

Steinmetz, Katy. "Why Transgender People Are Being Murdered at a Historic Rate." Time, 17 Aug. 2015. Web. 07 Nov. 2016.

Zimman, Lal. "Trans Pronoun FAQ, Part 1." Medium Trans Talk. N.p., 29 Aug. 2016. Web. 4 Nov. 2016

“Fish Cheeks

Megan Martino is a first year student from Novato, California and an English major at SF State. She loves to engage in discussion about literature and movies, and is a very enthusiastic person in general.

She also loves learning about Zen Buddhism, recently having read a multitude of books that piqued her interest; she only wants to learn more! She admires the dignified and disciplined practice, and sees new benefits from the philosophy everyday. As soon as possible, Megan plans to tour Australia in a modified four-door, with a mattress where the backseats belong and a storage rack on the roof. If you care to, you should ask her about her Rolling Green House™ idea; she's really excited about it!

COMMENT FROM GTA, SAVINA PALMERIN:

Megan’s essay is a testament to both the revision process and the rhetorical analysis genre. She built a strong foundation for her essay by paying close attention to the rhetorical moves in the text and researching Tan’s background. Megan incorporated ethos, pathos and logos in order to build on her arguments. Megan was able to maneuver the essay with ease as we built a community in our classroom to have open discussions about race issues in America. She also trusted her own voice and explored what she noticed in the text, thus making what she noticed an important element in writing this essay. This, along with Megan’s attention to organization made for a comprehensive analysis of Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks.”

Tan uses vivid details about “...the strange menu” her mother creates and the eating habits of the dinner guests in order to juxtapose the two families present at the meal. Food and dining rituals can define a culture, so when Tan uses language of disgust to describe the food her mother serves, it is as if she is disavowing her own culture through a rejection of her mother’s menu and her family’s eating practices. Tan describes the prawns as “fleshy” and the rock cod as “slimy” with “bulging fish eyes.” She seems to be adopting the disgust exhibited by Americans when they contact this cuisine. She further describes the mannerisms of her relatives and that of the white family, showing how her Chinese family grabs at their feast while the white family patiently waits for the dishes to be passed to them. Sensitive readers are aware that the mannerisms of the Chinese family are not a sign of rudeness but are merely a result of distinct cultural development. However, the characters in the story find it difficult to accept practices that contrast with their norms. Tan captures this sentiment simply: “Robert grimaced.” Robert, the minister’s son and Tan’s love interest, does not voice his discomfort for fear he may insult his hosts. Yet, young Amy Tan recognizes the look and feels heartbroken and ashamed of her heritage.

Tan knows her guests were uncomfortable and believes it is because they find her culture crude; she blames her heritage rather than the unaccepting attitudes of the minister’s family. The minister, Robert symbolizes white American society as a whole. His inability to embrace another culture represents America’s rejection of alternative identities on a larger scale. Although he eats the dinner prepared for him and his family, he is not grateful for the meal. This symbolizes the reluctant tolerance of American families, and the xenophobic undertones that persist, which generate national social tensions. Robert’s grimace is an example of this. While he never explicitly states his disgust with the Chinese meal, his small, ungrateful gesture indicates his intolerance of the Chinese culture.

Robert’s rejection is clearly difficult for Tan, and her feelings of alienation only worsen as the evening progresses. When Tan recalls, “I was stunned into silence for the rest of the night,” it captures how with each exposed cultural difference, Tan becomes torn between the two sides. However, by the end of the story, she is able to feel gratitude for her mother and her culture. Her final line, “For Christmas Eve that year, she had chosen all my favorite foods,” reveals how Tan finally embraces her own identity, which she had rejected throughout the meal. Because she was preoccupied with her dinner guests’ repulsion, she did not take one moment to enjoy the meal her mother had prepared especially for her. The grotesque descriptions in the first paragraph allude to the fact that Tan is disgusted with the meal in the presence of another culture, but the last line indicates that Tan savors such a meal when safe within her own culture.

While she loves her family and culture, she also knows they are being judged for their dining rituals. She recalls how, at the time, she thought her family was being ignorant. But as she grew older, she slowly realized her family’s behavior was simply a refusal to reject their culture in order to make unaccepting people more comfortable. Her mother not only recognizes her daughter’s distress during the meal, she uses it as an opportunity to connect. She tells Tan that when she was growing up, she could not fathom ever being as culturally involved as her relatives. Yet, Tan’s mother eventually realized that the principle of culture and family is more important than any individual’s opinion. Preserving family traditions is what keeps culture alive, and the act of preservation brings families closer together. She tells her daughter that although she wants to look American on the outside, her roots will always be Chinese. As a fourteen year old, Tan doesn’t fully understand her mother’s sentiment, but she matures to discover the truth of it, a theme she continues to explore it in her writing to this day.

“Fish Cheeks” is exemplary of problems that are found within every culture that has immigrated to Eurocentric nations. Allowing yourself to be immersed in your own or another culture can be surprising and rewarding, similar to how Tan feels when her mother promises that one day she would reclaim their tradition and heritage. As a grown woman, Tan writes this story as a social commentary that explains the impact that a lack of cultural acceptance has on individuals, particularly children. Tan is able to artfully explain her personal struggle as a Chinese American without explicitly condemning the white culture that rejects her. That ability allows her to inform and connect with readers about existing immigrant struggles, reminding us to be compassionate and tolerant of cultural differences.

Tan, Amy. “Fish Cheeks.” The Opposite of Fate: A Book of Musings. Putnam. New York, NY. 2003. Originally published in Seventeen magazine, 1987.

Down to a Trio

Jan Michaela Yee is a first-year student at SF State. She was born in the Philippines and moved to Hayward, CA with her family at age five. Ever since she was little, she has loved to draw because every stroke of her pencil gives her a freeing feeling, which makes her happy. Music is also a huge part of her life as she has learned to play many string instruments, such as violin and guitar, which brings the people she loves closer together. During her free time, she enjoys doing various activities; it usually depends on how she feels that day. Whether watching anime, playing with her dog, or spending a day playing video games, boredom is Jan’s kryptonite. Her many hobbies teach her about the world, and applying that knowledge to socialize with different kinds of people is what she values the most.

COMMENT FROM LECTURER, OMAR MARK ALI:

For their first major essay in English 104, students were asked to tell a story about themselves. This can be intimidating, especially at the start of a semester, but as we brainstorm and draft, their writing always starts to take on a deeper meaning, and in sharing these stories through peer-reviews, we all start to feel a little closer. Michaela tackled this assignment head-on, not only telling us about the very personal experience of her mother’s passing, but also making the reader feel a part of the story through a display of skills, such as specific details, dialogue, and relating her personal thoughts. Throughout, you are emotionally moved, not just by the content, but by the very words on the page.

On weekends, she’d take me to hunt for adventures. Garage sales would pile up in the Penny Saver on Saturdays, and we had to be there early to get all the “good stuff”. I was a third grader, so homework wasn’t a problem on weekends. We’d spend hours together driving around streets I’d never been to before. It was difficult to even remember where we were, but we always found our way back home together.

I spent so much time with her, it feels like a blur. As a child, I never thought about how much time we spent with each other, or how much fun the time between brunch and afternoons felt. When she’d ask if I wanted something to eat, I’d always get the french fries I wanted. One day, we were driving home and she casually asked me, “Mikee, what are you going to do when I die?” At eight years old, that wasn’t something I’d thought about often or something I’d be able to answer easily. I softly replied, “I’d be sad.” She changed the subject after that, and I didn’t realize how serious her question was. Those memories still feel like yesterday.

My mom’s first few days in the hospital are days I hardly remember. Our time going to garage sales and car rides was all I thought about as I sat in her hospital room. Nobody told me why she was there.

I was simply told, “She’s sick.” I thought cancer was like a cold - the type of sick that was gone after a few days. As time went on, I found out that wasn’t the case. One day she’d look completely fine and the next she’d contort with pain. That year, we spent a lot of time together while she was sick in bed. It was difficult for our family to be surrounded by worry and grief most of the time.

A year later, my father told my sister and I that our mother was getting better, feeling stronger and healthier. I kept hearing “Breast Cancer Survivor” and I proudly referred to my mom as one. I thought I was beginning to understand her condition, and the next few stages of cancer confused me. I decided to be less observant and ask less questions about what this illness was because my heart fell apart every time she went back to the hospital. I didn’t want to know.

Though her condition was limiting, we continued to have our adventures. Instead of garage sales, she’d take me with her to the hospital for check-ups. There, we talked about my hopes and dreams, and she advised me on situations I might encounter one day. We met patients and nurses whom we both considered friends. We had happy times there that almost made things seem normal again. The next couple of years were like a rollercoaster ride; but every ride has an end.

It was almost midnight and the red flashing lights reflected on the walls of our house. Her health was worsening; the tumor had spread throughout her body. I had never seen my dad cry before. He stood in my bedroom doorway and tried to break the news as gently as he could. “Mama’s dead.” he said. It was too much to handle. I hugged my dad with my tears falling on his shirt, and he led me into her bedroom. I pretended not to see the gurney set up in the living room. My sister was kneeled on the ground next to my mom’s bed, and I stood there with tears in my eyes trying to believe every moment was a dream.

The next morning when I got up my mom wasn’t home. My dad was already awake and told me she’d been taken somewhere. He said she was in a better place and everything was going to be okay. But I wouldn’t listen. Instead, I pretended last night had never happened; I somehow convinced myself that my mom was out buying groceries, just as she normally would, and was just taking awhile to come home. It took a while to believe she was really gone.

Not having a mom in my life changed everything. The smell I’d come home to wasn’t as aromatic as it used to be; holidays were busier with my sister and I doing all the shopping; the family dinner table was set for three, instead of four. It was hard to endure the days we used to celebrate together: my parent’s wedding anniversary, my mom’s birthday, and especially Mother’s Day because we were all reminded of that night. The only thing that kept us going was that we still had each other and felt mom was with us in spirit.

One night, I couldn’t sleep. I closed my eyes and when I was finally about to enter REM state, I felt a stroke on my forehead. My eyes remained closed, but I began to see a clear image of what was happening. I was in a meadow, under a shady tree. I subconsciously knew I was dreaming, but I still wanted to know what was going on; and looking straight up into the blue sky, there she was. I was lying on my mom’s lap, and she was stroking the hair off of my face, just as she had when I used to take afternoon naps. I asked her, “Ma, what’s happening?” She didn’t answer my question, only replied with her tender voice to go to sleep. Her presence felt so real - I could feel her spirit in my room trying to comfort me. Just as I was beginning to make sense of what was happening, everything began to blur and darken, and my mom started to leave, walking toward a door of shining light as bright as heaven. I asked her where she was going, and she gently replied, “It’s okay Mikee, just go to sleep. I’ll be right here if you need me.” The second she closed the door I woke up. I didn’t quite know how to react. I was in shock, the tears falling from my eyes.

Months later, I continued to have dreams about her. Some were sad, but the most of the time we had fun. I realized that even though she and our memories had passed, she would always be within me. One night we would be racing through a sea of monsters, and in the next dream we’d be shopping in the biggest mall I could imagine. Our adventures lasted every night I went to bed, and I knew she was looking out for me during the day.

As the years went by, our family trio was more than okay. Though the holidays were still hard, each year being together felt more comforting than the last. Our birthdays were celebrated with more memories than gifts. On weekends, we’d watch movies together and play with our dog. I’d come home from school, and my dad would ask me, “How was school?” I’d tell him all about my tests, my orchestra class, and even one thing I’d learned that day. The house began to have that sweet and savory aroma again; only now it was the three of us making the meal alone.

Benefits of Bilingual Education

Nimiksha Mahajan is an International Student from India majoring in International Business, with a passion for literature. It is her dream to combine her knack for business with her love for reading and writing and create a successful business one day. She is fascinated by diversity and guided by curiosity. She wants to travel the world - not in the “a fancy world tour” kind of way but in the “I lived like a local” kind of way. And she wants to learn all possible languages (currently fluent in three and on her way to mastering French) and musical instruments (mostly guitar, piano and violin). She is an absolute adrenaline junkie who loves roller coasters, adventure sports and basically anything with a mind-boggling thrill. While she lives for the outdoors, she is equally fond of the in-doors and will take a hot chocolate with a good book and the sun streaming through the window any day. She not only loves reading but also writing, poems in particular. They are her way of expressing her view of the world. And she absolutely loves pineapple on my pizza!

COMMENT FROM LECTURER, SARA FELDER:

Nimiksha provides a detailed argument advocating bilingual education, which in her view offers the most effective method to teach English to non-native speakers, while at the same time, empowers the immigrant community. A beneficiary of bilingual education herself as a native Hindi speaker, born and raised in India, Nimiksha’s perspective as an international student adds a vital voice to the issue. Our English 114 class embraced the theme of “Language and Social Justice,” and this essay, which went through a couple of drafts and peer review, completed the research unit where students picked a topic situated in the intersection of language and social justice. I was inspired to see Nimiksha’s clear writing, strong evidence, and fearless use of the counter-argument become itself a testimony to bilingual education and the benefits of speaking more than one language. We need her voice right now more than ever.

Bilingual education facilitates adaptation by improving the non-native student’s academic skills. Students with stronger academic skill are often more confident about themselves and have a better chance at adapting to their new environment. With this background, they often feel like they are capable of learning new things and are more open to adjusting into the community. An eight-year study conducted between 1984 to 1991 of the Longitudinal Study of Structured English Immersion Strategy, Early-Exit and Late-Exit Programs for Language-Minority Children, validated by the National Academy of Sciences says that “those students who received more native language instruction for a longer period not only performed better academically, but also acquired English language skills at the same rate as those students who were taught only in English.” (education.stateuniversity.com) Also, a 2004 study by psychologist Ellen Bialystok and Michelle Martin-Rhee proved that “bilinguals seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles” (Bhattacharjee). This suggests that a bilingual education enhances all students’ learning abilities, while also dismantling barriers between different cultures.

This teaching method often assists in bridging the gap between different communities by improving a child’s cognitive skills. Cognitive psychologists Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky define cognition as “the mental activity and behavior that allows us to understand the world” (Piaget and Vygotsky). When the brain hears or sees a word, it starts conjuring possible outcomes before the entire context is heard. The sound of a word is broken down by the brain, facilitating it to guess the word even before it is completed by activating different words that match the signal. For instance, when one hears “to”, words like “towards” and “tonight” automatically come to their mind. For bilingual students, this activation extends to two different languages resulting in quick and better interpretation of words and symbols. Research done by Ellen Bialystok and Michelle Martin Rhee at York University in Toronto shows that bilingual children have better ability to “deal with conflicting visual and verbal information” (Deussen). A student with strong cognitive skills can better interpret a situation and understand the varied implications. It is with this ability that students often understand of the world and the different people around them that adaptation becomes easy. By building strong cognitive skill sets in students, bilingual education prepares them better adapt in foreign communities.

Bilingual education often reduces drop-out rates. Often among non-natives, there is a fear that coming from a language other than English will subject them to prejudice or obstacles in their education. This fear, coupled with the hardships non-natives face coming from a different background, sometimes drives them to drop out of schools;

limited English proficient students are less proficient in core academic skills, which may make later classes more difficult, cause placement in less rigorous tracks of study, and raise dropout rates, lowering eventual educational attainment and human capital (Chin).

Students who are only proficient in their native languages often have difficulty with higher level academic curriculum and often drop out of school. Instruction in two languages relieves this issue and helps prevent non-native students from dropping out. “Bilingual education has heightened awareness of the needs of immigrant, migrant, and refugee children” (Porter). Bilingual education helps immigrant and refugee children learn English in order to succeed academically. Bilingual education values English as equally important as a second language, which enables students to develop more advanced language skills. No student is made to feel like an outsider as they are all given the same chance to acquaint themselves with the host language and culture. Bilingual education strives to go the extra mile to makes students feel welcome in the community, motivating those students to learn and make more meaningful contributions to that community.

With practical skills and knowledge of the culture and language of a place, a student is bound to feel more comfortable and confident, interacting with the community. Bilingual education, gives students this confidence for more than one language and community. Professor Leonardo De Valoes, an academic who speaks many languages fluently, says “our language is the most important part of our being.” It is important to learn other languages, other forms of communication besides our own in order to learn about other peoples and cultures. One important argument is that people can learn from their own mother tongue as this is a basic concept of identity. If people forget their first language, they lose a part of their background. Bilingual education focuses on achieving this objective while making students proficient in the dominant language or English. Like soil to a tree, bilingual education helps one stay connected with their roots and gives them a chance to grow and evolve in a diverse community.

Immersion in two languages at the same time is also an incentive for immigrant parents to educate their children as they American English, which helps them adapt in the US but they also stay connected to their linguistic heritage. With an increase in immigration, it is important that immigrant children receive an education that caters to both their native language and the language of the land. “For immigrant families and communities, raising bilingual children who can speak the language of their family and friends back in their country of origin preserves important relationships, traditions, and identity. At the same time, highly developed English skills provide the ability to participate fully in “mainstream” American life” (Deussen). Children are fluent in their home languages also master English language, which new opportunities and the possibility of relationships with people in other communities and countries

However, language experts believed at a certain point hat bilingual education jeopardized one’s chances of adjusting in foreign communities by limiting their linguistic skills. In the 20th century, “researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child’s academic and intellectual development” (Bhattacharjee). The critics felt that children would be confused as to which language to use when and would mix them up. But Bhattacharjee argues,

There is ample evidence that in a bilingual’s brain both language systems are active even when one is speaking only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn’t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles (Bhattacharjee).

Bilingual education teaches the student how and when to use this muscle in their brain for better understanding. This challenge strengthens not only one’s language skills but also their overall academic skills. With a better understanding of the diverse culture and better interpretation of the host language, one can settle in more easily.

While the benefits of bilingual education are clear to some, others still argue that bilingual education should not be practiced. Dr. Rosalie Porter, formerly a bilingual teacher, says bilingual education is a “wrong-headed theory” that doesn’t work. She believes that “structured immersion”, where “children initially are taught English in separate classrooms for part of the day, along with others who grow up speaking a different language at home, but are quickly thrust into classrooms where the teaching is in English” is a better approach of teaching for schools. “Most children in structured immersion can get up to speed in two years; with bilingual education, we’ve seen that it takes kids three to six years to mainstream” (Peek). Here, Dr. Porter argues that bilingual education is not an effective program and claims that there are better alternatives, which are shorter and more efficient. Despite Dr. Porter’s claim, bilingual education is better than alternatives because the alternatives like structured immersion, prioritize English over other languages, which is not justified in a culturally diverse country where the immigrant population is on a rise. Bilingual education might seem to be a lengthy process, but it does ensure quality linguistic learning which should be every schools main goal. “We don't do kids any favor by shoving them into English as fast as we can,” says Todd Butler, a teacher with more than a quarter-century of experience. “The research shows very clearly that the longer we can give them support in their language, the better they're going to do not just in elementary school but in secondary school as well” (Jost). Education is not about one-size-fits-all and bilingual education with its slow and steady pace helps more students learn and adapt.

Another majorly argued reason against bilingual education is that it is too expensive. According to a study by Boston University’s Christine Rossell, “Texas schools with a bilingual program spend $402 more per student than schools without a bilingual program. Other studies find that bilingual education costs $200 to $700 more per pupil than alternative approaches” (Peek). Authorities argue that this kind of funding cannot be justified to teach a language that is not dominantly used. That argument is not a strong one because firstly, it is morally unjustified to not invest in the success of every student for future of a country. It is shortsighted because bilingual education programs are investments in human capital. As the school system adopts bilingual education programs, they are investing in the students’ skill sets, which are in high demand in today’s globalized economic world.

The benefits of bilingual education far exceed its cons. It not only ensures that students’ language skills will stick with them for life, unlike English-only learning programs, it also prepares all students with stronger academic and critical thinking skills, and greater potential for success. Extensive research provides strong evidence to support bilingual education, already enough incentive to introduce bilingual education in schools; and with more research, we will only see more incentives. Bilingual education is clearly a beneficial investment for our students and our country, and hence a program all schools should introduce.

Works Cited:

Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit. “Why Bilinguals Are Smarter”, The New York Times. March 17, 2012.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/opinion/sunday/the-benefits-of-bilingualism.html. November 11, 2016.

Bialystok, Ellen (York University). “Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent”. Bilingualism: Language ad Cognition, Volume 12, Issue 1. January 2001. The Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728908003477. November 10, 2016.

Carr, Sarah. “The Reinvention of Bilingual Education in America’s Schools”. Schooled, With Columbia Journalism School Teacher’s program. January 5, 2015.

http://www.slate.com/blogs/schooled/2015/01/05/bilingual_education_the_promise_of_dual_language_programs_for_spanish_speaking.html. November 15, 2016.

Chin, Aimee. “Impact of Bilingual Education on Student Achievement.” IZA World of Labor. March 2015. http://wol.iza.org/articles/impact-of-bilingual-education-on-student-achievement.pdf. November 18, 2016.

Deussen, Theresa. “Treating Language as a Strength: The Benefits of Bilingualism”, Educationnorthwest.org. December 18, 2014. http://educationnorthwest.org/northwest-matters/treating-language-strength-benefits-bilingualism. November 11, 2016.

Google.com Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Languages_of_the_United_States

Haynes, Erin. “Heritage Beliefs”.

http://www.cal.org/heritage/pdfs/briefs/what-is-language-loss.pdf. 2010.

Iyer, Aparna. “The Disadvantages of Bilingual Education That Really Make Sense”. September 2, 2016.

http://www.buzzle.com/articles/disadvantages-of-bilingual-education.html. November 15, 2016.

Jost, Kenneth. “Bilingual Education vs. English Immersion”. http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresrre2009121100. December 11, 2009.

Marian, Viorica and Shook, Anthony. “The Cognitive Benefits of Being Bilingual” October 31, 2012. The Dana Foundation. http://dana.org/Cerebrum/2012/The_Cognitive_Benefits_of_Being_Bilingual/. November 15, 2016.

Mavis E. Hetherington. Ross D. Parke, “Child Psychology: A Contemporary Viewpoint” Chapter 9 “Cognitive Development: Piaget and Vygotsky”. http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/0072820144/student_view0/chapter9/index.html

Peek, Liz. “Bilingual Education: Toss It and Teach Kids English”, The Fiscal Times. August 25, 2010.

http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Columns/2010/08/25/Bilingual-Education-Does-Not-Work.

Porter, Rosalia Pedalino. “The Case Against Bilingual Education”, The Atlantic. May 1998 Issue.

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1998/05/the-case-against-bilingual-education/305426/. November 10, 2016.

TEDxAms Blogsquad. “The Different Brain of a Bilingual”, TEDX Amsterdam. http://tedx.amsterdam/2012/08/the-different-brain-of-a-bilingual/. November 11, 2016.

Valoes, Leonardo De. “Importance of Language – Why Learning a Second Language is Important”. http://www.trinitydc.edu/continuing-education/2014/02/26/importance-of-language-why-learning-a-second-language-is-important/. February 26, 2014.

Zelasko, Nancy F. “Bilingual Education - Need for Bilingual Education, Benefits of Bilingualism and Theoretical Foundations of Bilingual Education”. http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1788/Bilingual-Education.html.

The Analytic Perspective of Ocean Change

Ivan Manriquez, Jr. was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. He attended Montebello High School and is a freshman at SF State. Ivan decided to major in Astrophysics when he visited the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. There he learned about magisterial truths and insights, including the fact that we have chemical traces to the stars in the heavens. This inspired him to investigate the cosmos. Ivan’s biggest interests include Earth Science, Climate Science, Physics, Computer Science, Mathematics, Astronomy, and Philosophy. He loves having intellectual discussions and would talk to anyone.

He also loves reading a wide range of topics. Some of his favorite books include: Native Son, The Art of Living, Meditations, and Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. He enjoys a good run to the beach and meditating in nature. Ivan believes, as Buddha suggests, “The mind is everything, what you think, you become.” Ivan is part of the Guardian Scholars Program which helps foster youth excel in college. His biggest goal is to make a grand scientific breakthrough to help humanity.

COMMENT FROM LECTURER, PHILIP KLASKY:

Ivan Manriquez' paper is an excellent example of how SFSU students are giving serious, science-based thought and analysis to the challenges presented by global climate destabilization and its wide ranging impacts.

INTRODUCTION

This paper is concerned with the four main contributors to oceanic destruction: greenhouse gas emissions, overfishing, oil spills, and tourism. Before examining oceanic changes, I will provide a brief history of climate change research, define climate change, and determine its main cause. With this context established, I will turn to the main Earthly systems affected by climate change: the oceans. Human greenhouse gas emissions exacerbate climate change and have led to oceans’ exponential growth in acidity and its decline in species. Additionally, oil spills create disadvantages to the biology, ecology, and geology of the oceans. Overfishing is yet another example of human behavior that distresses oceans and endangers a major human food source. Finally, tourism and modern developments by the coastlines put coastal ecosystems at risk. These anthropogenic transgressions must be reversed, if possible, or prevented in the future. This work will culminate in a discussion of the climate justice movement, its many forms, and the ethical imperative the movement promotes.

Since the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century, humans have relied heavily on coal to power engines and produce goods. Humans predominantly used coal because it was a stable source of energy, yet they underestimated the hazards of coal procurement and usage. Thus, humans kept damaging ecosystems to find coal. It wasn’t until the 1890’s that a Swedish Chemist by the name of Svante Arrhenius proposed a paper titled, “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground,” which “pinned down the workings of the greenhouse effect and laid the scientific basis for the emissions cuts being debated to this day” (Clark). This heavily criticized, groundbreaking paper was known to originate the concept of climate change. The notion of climate change was dismissed until the late 1950’s, when scientists finally began gathering data concerning the concentration levels of CO2 in the atmosphere. The 1960’s provided some computer models and simulations about the possible rise of CO2 in the atmosphere, and this was confirmed in the 1980’s when scientists found that the planet's temperature was increasing exponentially.

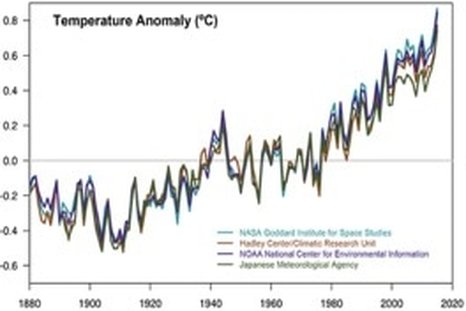

Over time, our methods allowed climate scientists to analyze and answer basic questions about the Earth’s climate. Furthermore, scientists were able to deduce how weather patterns correlate with the Earth’s changing climate, and therefore develop a definition of climate change. According to NASA,

Climate change’ encompasses global warming, but refers to the broader range of changes that are happening to our planet. These include rising sea levels, shrinking mountain glaciers, accelerating ice melt in Greenland, Antarctica, and the Arctic, and shifts in flower/plant blooming times (ClimateNASA, climate.nasa.gov/evidence).

When asked what causes climate change, “97% of climate scientists agree that climate-warming trends over the past century are very likely due to human activities” (NASA). Science academies, medical associations, and affiliates concur that humans are the root of climate change and that the threats posed by climate change are growing due to complacency and inaction. For example, The Geological Society of America states,

we concur with assessments by the National Academies of Science (2005), the National Research Council (2006), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007) that global climate has warmed and that human activities (mainly greenhouse gas emissions) account for most of the warming since the middle 1900s" (2006; revised 2010).

Global climate change undenabily affects oceanic ecosysytems and oceanic biodiversity around the world. Greenhouse gases toxidify our planet and our failure to curb our emissions will inevitably result in oceanic destruction. This paper will continue to reveal how anthropogenic emissions are causing the oceans to acidify, and will examine the effects of human behavior, specifically overfishing, oil spills, and tourism, on oceanic wildlife and coastlines.

METHODOLOGY

I derived a majority of my research from scientific magazines, such as Science Magazine and The Earth Island Journal. Additional information came from outlines on climate change, climate justice, and human history assigned in the class, “Race, Activism, and Climate Justice” at San Francisco State University. Articles and texts I have utilized include, “The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution,” “The Introduction to This Changes Everything,” and Earth by Bill McKibben. Lastly, I employed reputable websites focused on climate change like ClimateNASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website, and The New York Times website.

BODY

The oceans are being destroyed by anthropogenic emissions of CO2. During a lecture in “Race, Activism, and Climate Justice” it was stated, most of these emissions come from the production of electricity; about thirty-one percent comes from burning fossil fuels, mostly coal and natural gas. Twenty-seven percent comes from fossil fuels for cars, trucks, ships, trains and planes. Twenty-one percent comes from burning fossil fuels for energy and chemical reactions to produce goods from raw materials. The remaining percentage results from businesses and homes burning fossil fuels for heat and handling waste, and emissions from livestock such as cows, agricultural soils, and rice production (“Source of Greenhouse”).

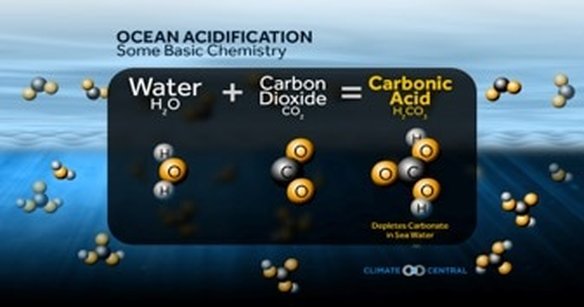

One critical group of impacted marine life includes shells and skeletal species of the sea. According to Oceanus Magazine, “A new study has yielded surprising findings about how the shells of marine organisms might stand up to an increasingly acidic ocean in the future. Under very high experimental CO2 conditions, the shells of clams, oysters, and some snails and urchins partially dissolved” (Madin). Some species such as oysters, snails, and sea urchins can lose their shell over time, which will lead to their extinction. According to postdoctoral scholars at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Anne Cohn and Dan McCorkle,

[they] raised 18 species of marine organisms that build calcium carbonate shells or skeletons. Then we exposed the tanks to air containing CO2 at today’s level (400 parts per million, or ppm), at levels that climate models forecast for 100 years from now (600 ppm) and 200 years from now (900 ppm), and at a level (2,850 ppm) that should cause the types of calcium carbonate in shells (aragonite and high-magnesium calcite) to dissolve in seawater (Madin).

Another high-risk deep-sea species is deep-water corals. The importance of healthy deep-water corals is often underestimated, but these corals provide more than homes to oceanic species. According to Science Magazine, “Effects on deep-water corals are of particular concern, because their three dimensional aragonite structures form vast gardens that support highly diverse communities and provide key nursery habitat to commercial fishes” (Levin). Not only are the homes of marine species affected, but their nursery homes are put at risk as well. If we keep following this pattern, fish species will lose their nursery homes, and they will have trouble finding locations to lay their offspring, which can jeopardize the species as a whole. If the ocean keeps acidifying, eventually the aragonite structures will dissolve completely and slowly wipe out the fish species that rely on those structures. This can harm humans who heavily rely on fish as their main food source. It is clear that anthropogenic CO2 emissions are the main reason why the oceans are acidifying. If we continue to rely on un-renewable sources of energy, the oceans will become acidic enough to destroy a plethora of marine species, which will jeopardize the homes of a multitude of fish and damage one of our biggest food resources.

Furthermore, oil spills are a repercussion of human activity that affect the marine vertebrates and marine ecology of the oceans. Oil spills tend to have disastrous effects on the oceans because they alter the oceans’ biology and ecology. Drilling for oil in the sea floor, or transporting oil across the sea, can lead to water contamination and other devastating effects on marine life. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explains the danger of oil spills claiming,

Many birds and animals ingest oil when they try to clean themselves, which can poison them. Fish and shellfish may not be exposed immediately, but can come into contact with oil if it is mixed into the water column. When exposed to oil, adult fish may experience reduced growth, enlarged livers, changes in heart and respiration rates, fin erosion, and reproduction impairment. Oil also adversely affects eggs and larval survival (National Ocean Service).

In May 2015, Santa Barbara experienced a pipeline rupture, which afflicted the surrounding environment and the Pacific Ocean. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “a 24-inch pipeline rupture occurred earlier in the day near Refugio State Beach in Santa Barbara County, California. A reported 500 barrels (21,000 gallons) of crude oil flowed from the shore side of Highway 101 into the Pacific Ocean” (National Ocean Service). This pipeline rupture caused havoc in the Pacific Ocean by contaminating the ocean and the marine animals. Despite the findings of the NOAA, some economic consultants believe there is an upside to oil spills. According to The Earth Island Journal, Todd Schatzki, vice president of the economic consultancy Analysis Group, wrote in pre-trial testimony, “when a spill occurs, new economic activity occurs to clean contained areas, remediate affected properties, and supply equipment for cleanup activities” (Mitra). Todd Schatzki’s argument was taken further when Gregory Challenger, another consultant at Analysis Group, suggested that the benefits of a 2004 oil spill into the Delaware River extended beyond an increase in economic activity. According to Gregory Challenger, “There was an estimate of 3,000 birds affected by the oil, and 13,000 birds not shot by hunters because of the closed off area. We don’t get any credit for that, but it’s hard to deny that it’s good for birds not to be shot” (Mitra). Challenger’s logic is unsound. Oil spills generate jobs because cleaning up an oil spill and containing an oil leak is strenuous work. However, the damage to oceans and to marine life threatens the jobs of fisherman. Furthermore, the oil spills destroy oceanic ecosystems and degenerate a main human food supply. The cost of oil spills simply outweighs the slight uptick in economic activity. Despite the claims of consultants like Schatzki and Challenger, oil spills endanger sea life and therefore endanger us. Unfortunately, oil spills and greenhouse gas emissions are just two examples of detrimental human behavior.

Another case of overfishing involves the Pacific blue fin tuna. The blue fin tuna are exceptionally powerful and crucial for ocean bio-diversity. They grow to be twice the size of a lion and are as fast as a gazelle. Unfortunately, because of tuna’s high market value, droves of profit-seeking fishermen routinely catch an irresponsibly high volume of tuna. According to The New York Times, “in the case of Pacific Bluefin, weak international regulations have failed to stem the toll. Now, where every 100 fish once thrived, fewer than three remain. Without rapid, coordinated action by the major fishing nations, Pacific Bluefin tuna face commercial extinction, becoming too rare to catch profitably” (Lubchenco). In essence, we are catching so much tuna that it is no longer profitable. There is no financial incentive to continue overfishing this species, and if we do not immediately modify our practices, the Bluefin Tuna will go extinct.

While we continue to hunt specific fish species into extinction, other marine animals are unintentionally caught in fishing gear. Bottom trawling is a fishing method that involves setting a huge net on the bottom of the sea floor. Although it is an effective method of catching desired fish, it indiscriminately harms other marine life. According to Green Peace, “if the same technique were used on land, it would be like dragging a vast net across the countryside - crushing trees, farms and wildlife in the process - to catch a few cows” (“Overfishing – emptying our seas). This method is very destructive; it harms the environments of hundreds of species.

The final anthropogenic source of oceanic depletion involves modern development on coastlines and tourism. Humans live in the countryside, urban areas, and mountain areas, yet the most popular location for housing is by the beach. Additionally, there is a high demand for vacation time at coastal locations. As coastlines around the globe are progressively transformed into new housing, holiday homes, and tourist attractions, aquatic bionetworks and species are suffering. One devastating example of modern development and tourism is in the Mediterranean. According to the World Wildlife Fund for Nature,

Of the 220 million tourists to the region every year, over 100 million flock to the beaches. In less than 20 years, the annual number of tourists visiting the area is expected to increase to 350 million. The huge tourism infrastructure developments have dramatically altered the natural dynamics of Mediterranean coastal ecosystems. For example, more than half of the 46,000km coastline is now urbanized, mainly along the European shores. This infrastructure is a major cause of habitat loss in the region, and some locations are now beyond repair (WWF).

Climate justice is based on the idea that as humans fail to protect their environment, they are perpetuating injustice against themselves. Climate justice is “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development and enforcement of environmental laws” (Bullard, 4). The enactment of climate justice depends on unilateral, worldwide enforcement of environmental law. We must first attack CO2 emissions to stop the oceans from acidifying. The most effective action would involve an international treaty guaranteeing an end to our emissions by a date in the near future. Hoesung Lee, the chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, purposed such a treaty in Science Magazine. Lee states, “The goal is to achieve an international agreement to stem climate change.” This is a goal, which will be difficult to accomplish. The lives of millions depend on the collaboration of nations. On a national level, we can peacefully protest against climate change so our leaders take notice. However, the only way to save our oceans from acidifying further is to create an international bonding treaty to ease emissions of greenhouse gases.

Additionally, to employ climate justice, overfishing must be solved. We need simple yet stern regulations on how we fish and where. According to the World Wildlife Fund for Nature, “We must, implement and enforce better fisheries management, create and implement better fisheries policies, implement and enforce observers, look into the possibilities for Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification, implement and enforce more selective fishing gear” (“What Can You Do?”). Furthermore, we must protect the oceans from oil spills in order to advance climate justice. In order to accomplish this we must stop using oil; we must halt building oil pipelines because of the damage they cause. Oil is useful to humans, but it harms our climate and threatens our race in the long run. When oil enters the sea, marine life is threatened and greatly reduced. When this happens, we deplete our largest food resource. Finally, to employ climate justice, it is our duty to protect our oceans from tourism and development. This is currently a problem that lacks a solution. To stop people from purchasing coastal homes is almost impossible, especially those who are wealthy enough to purchase beachfront property. As of now, preventing tourism is equally impractical. Perhaps the only achievable preventative legislation would involve “vacationing sanctions.” Large tourist areas should have limitations regarding seasons for tourism and the amount of people permitted entry. The solutions offered here are just a few examples of possible steps towards climate justice. Humans have the power to bring justice to the oceans of the world; we must now find the will to do so.

CONCLUSION

We as a collective human species must realize the big issue at hand. The damaging impact of human activity on coastlines and ocean life is undeniable, the negative impact of oil spills on marine vertebrates is chilling, and overfishing is causing a decaying trend of fish. Because of our continuous emission of greenhouse gases, our entire planet is experiencing consequential effects. The oceans are acidifying exponentially, faster than ever, and just as Naomi Klein wrote in the introduction to This Changes Everything, “we must plan a strategy to attack this massive issue. Nothing poses this strong a threat to humanity and mass movements of people can make this happen” (Klein 6). In the end, humans have the power to control their own destiny and the destiny of generations to come. Will we choose oceanic justice over profits? Will we bring marine species justice? Only the actions of the masses will tell. Climate change and oceanic destruction is a continuing calamity. Failure to act will end coastal and marine life and therefore lead to a steady decline in human life, as we know it.

Works Cited:

Bullard, Robert D. The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution. Counterpoint. 01 Oct. 2005

Clark, Duncan. “Climate Controversies.” The Guardian, 14 February 2009.

“How does oil impact marine life?” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 21 Mar. 2014,

http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/oilimpacts.html.

Klasky, Phil, “Source of Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Class Lecture. San Francisco State University, Global C02 Emissions.

Klein, Naomi. Intro to This Changes Everything. Simon and Schuster, 2015.

Levin, Lisa and Nadine Bris. “The deep ocean under climate change.” Science Magazine. Special Issue. vol. 350, no. 6262, 13 Nov. 2015.

Lee, Hoesung. “Turning the Focus to Solutions.” Science Magazine. vol 350, no. 6264, 27 Nov 2015.

Lubchenco, Jane and Maria Damanakidec. “Save the Bluefin Tuna.” New York Times. 4 Dec. 2016.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/04/opinion/save-the-pacific-bluefin-tuna.html?_r=0.

Madin. Kate, Ocean Acidification: A Risky Shell Game: How will climate change affect the shells and skeletons of sea life? June 2010.

“Marine Problems: Tourism and Coastal Development.” WWF Global.

http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/tourism/.

McKibben, Bill. Eaarth. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2011.

Mitra, Maureen. “An Upside of Oil Spills”. Earth Island Journal. vol. Fall 2016.

NASA Climate. “Scientific Consensus Earth’s Climate Is Warming.” NASA. 13 Dec. 2016. http://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus/.

“Overfishing—emptying our seas.” Green Peace UK, Nov. 2014.

http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/oceans/problems/overfishing-emptying-our-seas.

“What Can You Do.” WWF Global.

http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/smart_fishing/stop_bycatch

Her Body, But Not Her Choice

Swetha is a second-year student at SF State from San Fernando Valley, and she adores the fresh change San Francisco has brought her. She started her undergraduate career majoring in Journalism, but she doesn’t think it will stick. She is passionate about feminism and implements this in her writing and life. She has always been fascinated with writing and hopes one day to write a book that will live on beyond her. Until then, Swetha is satisfied spending her days working on her degree, reading, and being a tea enthusiast.

COMMENT FROM PROFESSOR NAN BOYD:

Swetha wrote “Her Body, But Not Her Choice” in Women and Gender Studies 300: Gender, Race, and Nation - the Women and Gender Studies department’s GWAR class, a writing-intensive seminar required for all WGS majors and minors. During the semester, students develop skills to write a medium-length research paper by conducting research on a topic of their choice that relates to the politics of gender, race, and nation. Students are also required to effectively utilize an interdisciplinary, intersectional, and transnational analysis in relation to their topic. This isn’t easy! Many students interpret the transnational analysis to be about “over there” or outside the national boundaries of the United States, but a transnational analysis interrogates the function of the nation or nationalism in the production of gendered and radicalized meanings, which is what Swetha Pottam’s essay does so incisively — and well.

They have been turned over to the imagination of others,

and those imaginings are then allowed to reign over her body as law.

-Drucillia Cornell, The Imaginary Domain

India has always been a site of unique cultural practices and beautiful festivals that have sparked curiosity across the world. However, the reality of female sexuality in India is not as beautiful. Although Indian society reveres women and considers them equal, they are equal only in name. Contemporary female sexuality in India is repressed and ignored for the benefit of heteropatriarchy and the Indian nation-state. Women’s subjugation is enforced by a prevailing gender hierarchy in both the public and private spheres and is influenced by cultural practices, nationalism, and colonialism.

When Great Britain colonized India, they utilized a fraternalist approach to colonial administration, which enabled the subjugation of female sexuality (Keating 133). To engender a fraternalist relationship between the colonial administrators and leaders in Hindu and Muslim communities across the country, they first established the system of “personal law.” This system of personal law “was the codification and classification of marriage, divorce, and inheritance practices as laws that were based on each community’s religious texts,” (Keating 133). This system was unfair to women because it elevated religious laws over customary laws, which would have been more favorable to women.

After India gained independence, the Constituent Assembly recognized women’s equality because of women’s contributions to the nationalist movement; however, the Assembly’s promises of equality were never fully realized. When the time came to form the Constitution and create a mode of governance free from British involvement, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Indian prime minister, made it clear that he wanted to form an egalitarian democracy in which discrimination on the basis of sex, religion, and caste would be eliminated (Keating 130). Yet, after India gained independence, the new constitution was modeled after the systems of British colonial rule (strong centralized governance vs. the traditional Indian village level of governance) and Western political theory (Keating 135). They upheld the system of personal law, which separated the public and private spheres. The notion of equality and freedom operated in the public sphere while gendered relations of domination and subordination were practiced and even encouraged in the private sphere. By maintaining the system of personal law after achieving independence from Great Britain, avenues of discrimination against women remained open.

Simultaneously, the postcolonial sexual contract was formed, and thereby the subjugation of female sexuality was maintained for the sake of a unified state. The postcolonial sexual contract is derived from political theorist Thomas Hobbes’ “social contract” which asserts, “legitimate political authority is grounded in an agreement among equals in which citizens consent to exchange their natural freedom for the order and protection a government supposedly can provide,” (Keating 131). Carole Pateman, the author of The Sexual Contract, argues that in Western liberal democratic theory, the contract is a sexual contract as well as a social one.

The postcolonial sexual contract established a gender hierarchy and the legal and social subordination of women in the public and private sphere. The framers of the Indian constitution were aware of the failures of Western democracies to include minority groups and women and vowed that they would not do the same. Delegates understood that to create a democracy that serves all the people, they need “social, political, and economic justice for women” (Keating 134). Where did this go wrong? Delegates passed a legally enforceable fundamental rights measure that promoted equality among the sexes and barred discrimination on the basis of sex, race, religion, and caste. After enacting the measure, the Assembly had to decide what kind of state this free India would be. Nehru argued for a strong centralized state. Gandhi argued for a decentralized state to stay in line with the Indian practice of decentralized village-level governance (Keating 134). Despite dissent, the Assembly created a strong centralized government whose framework was drawn upon the British mode of colonial administration. The Assembly wanted the authority of the new Indian state to be respected, so they employed a strategy that returned to the familiar rhetoric of fraternity that the colonial administration relied upon to create consent and compliance within the nation.

Women and minorities suffered for the sake of a centralized government and unified state. Personal law detractors passed reforms that would end or relieve women’s subordination. For instance, in the 1930s, feminist nationalists pressed for changes to the Hindu personal law, and an INC Committee designed the Hindu Code Bill that would have introduced major reforms to laws regarding marriage and inheritance (Keating 139). Assembly members overturned the measures that were previously passed to protect women’s rights and the political inclusion of minorities. Despite the gains that the Constituent Assembly made regarding gender equality, the Assembly’s debates over proposed alterations of the personal law system solidified control over women in the interest of preserving fraternal solidarity. This was the impetus of the postcolonial sexual contract, and it is how discrimination against women has persisted despite the Assembly’s attempts to incorporate gender equality within the Indian political framework.

Assembly members argued that removing the measures was necessary to build a “homogenous” political sphere (Keating 137). Keating states, “The majority Hindus cast themselves in the role of the ‘responsible, easy-going, benevolent, and self-sacrificing elder brother, indulgent, protective, and accommodating of even the excessive and unreasonable demands of his younger and weaker brothers, the minorities’” (Keating 137). This is similar to the white savior complex because the majority Hindus took it upon themselves to “protect” women and minorities, similar to how white men decided to save people of color from themselves. By casting themselves in this role of the benevolent elder brother, they masked the fact that they were taking away promised power to women and minority groups, which impacted the control of women’s sexuality.

Under colonialism and anti-colonial nationalism, the politics of respectable sexuality served to reinscribe older social hierarchies. “Indian” tradition dictated the construction of gender and the construction of women in post-colonial society. (Sinha 1). After India achieved its independence, the nation and the discourse of sexualities worked together to create a new social arrangement. The new sexual discourse was crucial to forming the image of the modern Indian nation-state. This discourse not only suppressed “abnormal” sexuality but also heightened “normal” sexuality (Sinha 2). As a result, the “Indian” image prioritized family and heteronormative relationships above all other relationships. It was the building block of Indian society.

The rhetoric regarding female sexuality from 1891 to 1929 changed and matured into a force with institutional strength that maintained the “Hindu” and “Indian” image and restructured sexual relations that also upheld hierarchies of gender, caste, and class. Not only was this enacted through colonial administration, but it was also established through the legal realm as well. The “woman question” plagued nineteenth century Bengal but was settled when middle classes “accepted dichotomized lifestyle distinctions, i.e., home/world, spiritual/material, feminine/masculine” (Drew 31). Even though these distinctions were meant to express differences in equality, they worked to strengthen traditional gender roles and to further disadvantage women. Male agency continued to control women’s sexuality due to Britain’s policy of personal law. This subjection of female sexuality was evident in reproductive practices.

Women were regarded as objects or passive beings in patriarchal systems. A legal case during Indian colonial times illustrates this perfectly. Chew, the author of The Case of the “Unchaste” Widow, argues that women in a colonial setting were at the intersection of contested space between domination and subordination. English and Indian men debated womanhood and female sexuality (31). Chew’s analysis of the Kery Kotilany v. Moniram Kolita case exemplifies the aforementioned claim. In this lawsuit, a Bengali woman took a lover after the death of her husband, and subsequently bore a child. Her deceased husband’s cousin sued her, claiming that she violated the chastity she was supposed to uphold after her husband’s passing. The cousin hoped to overturn Anglo-Hindu legislation that allowed propertied widows to remain on the land of their former husband. These property laws were developed because colonialism changed the way in which people sustained themselves. Specifically, traditional joint farms disbanded and men had to seek wage-based employment. As a result, many resource-less widows were left destitute. Only the widows with resourceful relatives were able to exploit the obligations of “maintenance” (a system that required the heirs of the family to look after the widows and allow them to live the same life they lived prior to the dissolution of their marriage) and assert claims to their deceased husband’s property (Chew 33). However, a widow’s unchastity nullified her property rights. This case highlighted the sexual double standard placed on men and women. The notion of an “unchaste” man was unheard of because chastity was and still is a term “used to describe socially unsanctioned sexual activity by a woman” (Chew 32). The notion of chastity and unchastity dictated a woman’s life, whereas for a man, it mattered little. Sexual morality does not exist for men, and male-widowers were encouraged to remarry. Female purity was idealized in a patriarchal value system. “Unlike men, the case literature clearly establishes that for women, sexuality was intrinsically linked to property rights” (Chew 32). This case also highlighted how women were seen as property.

Culturally prescribed gender roles bind women and their bodies. The body is the site of emotions and experiences and also a site that is subject to social, political, and cultural constructions and regulations (Bannerji 124). This is due to a prevailing gender hierarchy that asserts itself in the public and private sphere. Women with more than two children are forbidden to receive anti-poverty subsidies and medical benefits (Hussain 36). The women’s movement advocated that reproductive rights were fundamental and included intimate issues such as their sexuality, whom to marry, how many children women choose to have, and how to protect their health. However, the unfortunate reality is that women often have no choice and their bodies “become pawns in the struggle between the individual, the family, and the state,” (Hussain 30). Female sexuality is controlled at the macro-level by policies and programs, while at the micro-level, it is controlled by male domination.

The entire reproductive process, from conception to childbirth, is shaped by patriarchy and male domination in the private sphere. For instance, in a study done by Sabiha Hussain, when women were asked about their family size preference, the majority of women negated the idea of a “desired family size” and said that expressing their desires does not necessarily mean it will be implemented (35). In this way, women’s concerns are ignored and invalidated for the preservation of the family.